Mathematicians love to generalize/extend ideas and concepts. There seems to be no limit to their creativity in finding ever more generalized versions of everyday concepts. From exponentiation first being shorthand for repeated multiplication, e.g.

Today we are going to see how mathematicians, in the attempt to make calculus rigorous, extended the concepts of a maximum and a minimum element in a set.

Supremum and Infimum the Basics

Ok, since we plan on extending the idea of a maximum and minimum values of a set, we should state explicitly what it means for a number

Definition: (Maximum) Let

- for any number

We denote the maximum value by

For example, if

Also, note that if

Not too bad so far.

Most sets don’t have a maximum value though. There are boring examples of this like the integers

First, notice that neither set has a maximum value

For example, consider 0.9999999999. If we naively said that 0.9999999999 was either

Even though neither set has a maximum, we can still find numbers that bound both sets (there are numbers larger than every element in

Now, did you notice that 1 seems to be a special value for both

For these two reasons we might say

Definition (Upper Bounds): Let

If the set

For example, 100 and 1.1 and 1.0001 and

Our next step is to turn our attention to a very special upper bound, the least upper bound.

Definition (Supremum): Let

- for any upper bound

If

We denote that supremum of

That’s it! Let’s look at some examples:

- If

- If

- If

- If

- If

- If

The supremum captures the idea that some sets “want to” have a maximum but never reach it. They get closer and closer to that almost maximum value, this value ends up being the set’s least upper bound, i.e it’s supremum.

Finding and then Proving the Supremum Analytically

I find that most confusion arises in proving our assertions about what the supremum of a set is. For example, how do we prove that

For this reason, we want an analytic way to understand the supremum. This will not only be good practice for up-and-coming topics like sequence limits, functional limits, and continuity, but it will also make our lives easier later on when we need to prove statements about the supremum.

Let’s trial some ideas.

Ideas are good

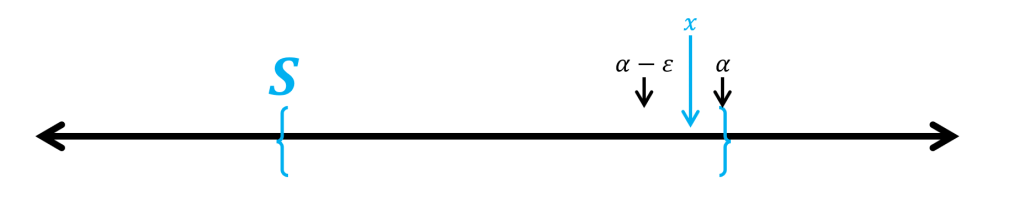

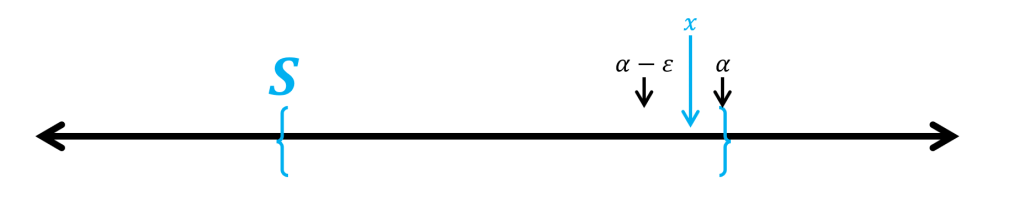

Let’s say that some set

If there wasn’t, then

Question: Was there anything special about subtracting

Theorem: (Proving Supremum using Analysis) Let

- for any

This probably seems like an overly complicated way to understand supremum, but all the theorem is trying to convey is the idea that we discussed right before it. That is, if we subtract any positive quantity (

Proof: Let

Forward: If

Let

there exists an

But, then

Backward: If

Let the

Property (1) takes care of the first part in the definition of supremum. What we have to do is show that

We let

But wait,

And just like that we conclude our proof.

Supremum and The Real Numbers

A critical fact is that the real numbers are closed with respect to the supremum. By this, we mean that any subset of the real numbers will have a supremum that is either a real number or infinity. We don’t need to invent more numbers to account for the supremum.

This is not a fact that the rational numbers enjoy. For example, if we take more and more digits from the square root of 2’s decimal expansion, we find that the following set of rational numbers

has a supremum of

Theorem/Pseudo-Axiom (Least Upper Bound Property of

See Least-upper-bound property – Wikipedia for more details and references.

In fact, I misled you at the beginning. We motivated the supremum by saying that it was a generalization of the maximum of a set; this is not the whole story.

Say we were interested in constructing the real numbers by extending the rational numbers. To do this we’d want `add in’ the irrational numbers `missing’ from

The beauty of this idea is that we don’t need to explicitly know what numbers are missing from the rational numbers! We don’t actually reference irrational numbers, only the rational ones in some set. And since all we know are rational numbers this is great! We then construct the missing numbers like

Archimedean Property

Let’s use the supremum and the least upper-bound property to prove what is known as the Archimedean Property.

Theorem (The Archimedean Property): For any

Proof: Let

For the hope of a contradiction, let’s assume that it wasn’t true that there was natural number

This would mean that the set of natural numbers

By using

Examples Galor

Let’s prove some of the claims that we made earlier. In all the proofs that follow, we will want to show that for any

The hard part is that our

If

Scratch Work: Well,

We now want to show that for any

Not quite, since we are given

Proof: Let

On the other hand, when

In either case we have shown

If

Scratch Work: The strategy is the same. Since every element in

As a hint, rewrite every element in

Proof: Let

Next, observe that for our

This concludes the proof!

A Quick Comment

Did you notice anything about how we started our two proofs above? No? Double check!

We started each proof by saying, “Let

Connecting Supremum to the Maximum of a Set

We began with the motivation of generalizing maxima and minima of sets. So it better be the case that when a set has a maximum value it equals it’s supremum. Indeed this is the case.

Theorem (Supremum and Maximum): Let

Proof: Let

Let

If ![I_2= [0,1],](https://s0.wp.com/latex.php?latex=I_2%3D+%5B0%2C1%5D%2C&bg=ffffff&fg=000&s=0&c=20201002)

Proof: Observe by definition

Ok What about the Infimum???

Up to now we have focused on the supremum and maximum. The infimum is to the minimum as the supremum is to the maximum. Meaning everything we stated has an analogous definition or theorem:

Definition: (Minimum) Let

- for any number

We denote the maximum value by

Definition (Lower Bounds): Let

If the set

Definition (Infimum): Let

- for any lower bound

If

We denote that supremum of

Theorem: (Proving Infimum using Analysis) Let

- for any

Corollary (Greatest Upper Bound Property of

*Note this is a corollary to Theorem/Pseudo-Axiom (Least Upper Bound Property of

Theorem (Infimum and Minimum): Let

The proofs are the same as those given for the supremum, so I defer them to you! I have to leave you something to practice with!

Closing Remarks

This article was a very, very non-standard way to describe the supremum and infimum of a set. However, I think it is instructive to build intuition. If you go to any other book on the subject, you aren’t likely to find a description like this. This is why I wrote it, after all, there are many great books on this subject already!

Oh, and at the start I asked: What on earth does

where

We’ll next encounter supremum and infimum when we start to look at sequences and limits.

Put your proofs for the infimum cases in the comments below!

Leave a reply to Let’s Get Real… Analysis (Part 3.2) Uniqueness of Limits – A Kick in the Discovery Cancel reply