Today’s our sixth article in the series Newbie at Number Theory. Today, Fermat’s little theorem. If you’ve read all my articles, then you would have seen a proof using Lagrange’s theorem in the setting of group theory. This time however, we show a proof that uses only tools that we have learned in the last 5 articles.

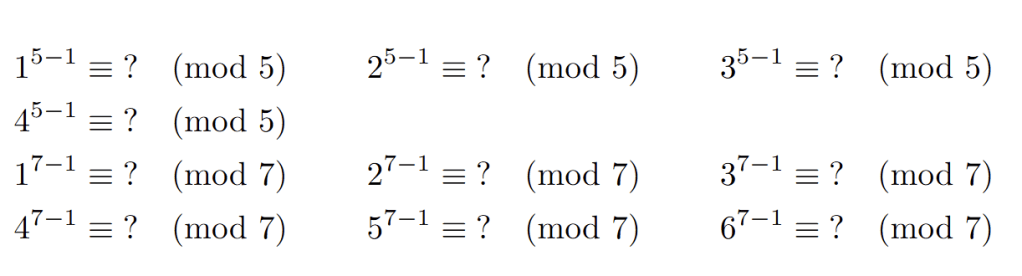

We will give two proofs of this theorem, but first… what is the theorem? Instead of telling you, I want to give you a chance to get A Kick in the Discovery for yourself. So… try these out (even if you use Wolfram Alpha):

Notice anything? If so, make a conjecture! Then try to prove it!

Hint: 5 and 7 are primes. The exponents are (PRIME) – 1. Try these with composite modulus.

Fermat’s Little Theorem

What I hope you noticed is that every one of the above gave

Fermat’s Little Theorem: Let

be prime and letthen

Equivalently, for any

Proof 1: (Click in the Discovery)

This one is really snazzy! It’s exactly the same idea that we used when we proved Fermat’s little theorem here. But this time without all the group theory shenanigans.

Let

We claim that all of these integers are different (mod p). To see this, let

implying that

Recap: We just proved that every integer in the set below is distinct (mod p), can you see why?

Let’s reduce this set of integers (mod p). Since there are p-1 distinct integers (mod p) in

How awesome is that????

Because of this the product of every integer in

Or using the factorial,

It sure would be nice if we could divide both sides by

And we are done! On to proof 2.

Proof 2: (Click in the Discovery)

I have a marvelous second proof of this theorem, but it’s too long and I could not fit it here.2

Closing Remarks

What a remarkable statement:

Give it a try! You’ll find that Fermat’s little theorem doesn’t work for composite moduli. However, Euler did find a generalization. But that’s a story for another day! See if you can work out what it might be!

See you next time!

Footnote:

Leave a comment