Last time we left off with a mystery… But before we get to that, a little introduction.

In your high school algebra class, you were probably given some equation like

Now, let’s ask a more difficult question.

Find all the integer solutions to the equation

So, I ask you:

How do we know there is even one solution? If there is, how do you find the solution? If there is a solution can there be more than one solution?

We will answer all these questions!

NOTE: When we say ‘solution’ we mean an integer solution.

Now back to the mystery from last time.

A Motivating Mystery (Taken From Here)

Let’s consider,

Are there any integer solutions? If so, can you find any? Give it a try!

I’ll wait…

Did you find any?

No?

Does that mean you didn’t try enough, or are there no solutions?

Ok, try this one, it’s almost the same:

Give it a go!

Did you find any this time?

Maybe x = -2 and y = 1: since

The first equation has no solutions whereas the second one has infinitely many solutions.

What’s the problem with the first one, why is there no solution? If you haven’t had time to think about it, give it a few minutes. Once you think you have a guess, use it to guess whether

Solution

Take a look at the left-hand and right-hand sides:

No matter what you choose for x and y, the left-hand side is even. The right-hand side is 1, which is odd. This is why there are no solutions. Since if there was a solution then we’d have the impossible statement: (Even Integer) = (Odd Integer).

Notice how this issue does not arise with

There’s a problem because there is no integer solution to

Why? Both

The issue is not 15’s and 21’s even/odd-ness, but their divisibility by 3:

So it seems important to consider what numbers are a divisor of both

For another example, consider the situation when

We conclude that

We therefore focus on finding when there are common factors between

Definition: We say two integers

andare relatively prime (or coprime) if they share no factors. Or, more simply, when

So, we might conjecture something like this:

Conjecture: If the equation:

This is indeed true. Actually, it’s even stronger than that! But first, Bézout’s Identity.

Bézout’s Identity

Bézout’s Identity: Let

andbe integers. If, then the equation:has an integer solution.

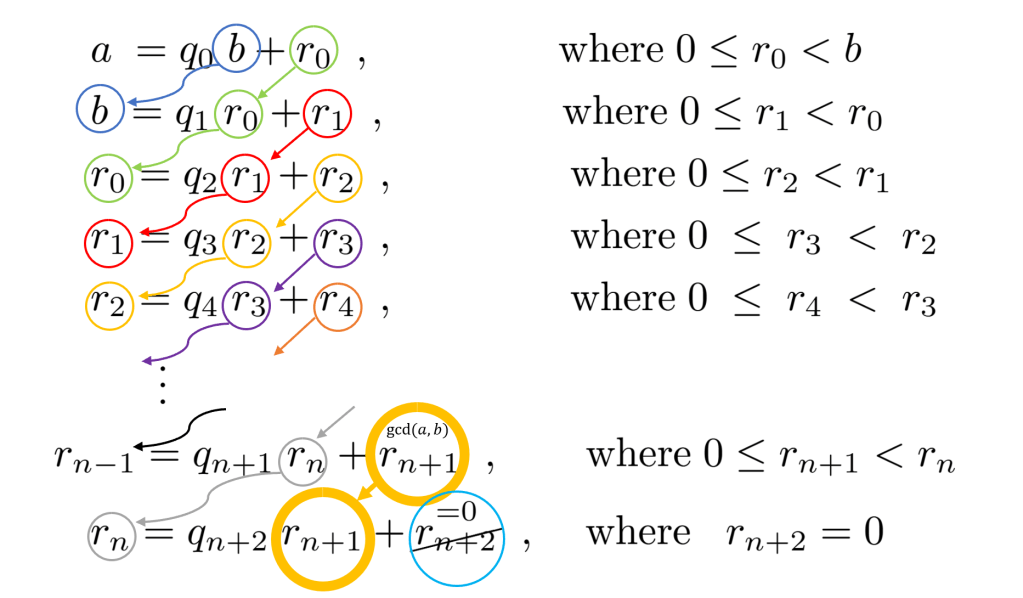

Proof Idea: We are going to rely heavily on the Euclidean Algorithm, so I recommend you take a moment to recall the process of finding

Here’s the color-coded schematic from last time:

Since we want a solution to

We ultimately want

The line above the second to last equation but we can deduce it would have been

Wait, we can plug this into our expression

Where we gathered all like terms.

Our game plan is to continue doing this until we reach the top equation with

Where the stuff and more stuff are integer expressions full of remainders

Let’s do an example.

Example

Our aim to to find integers

From last time, we saw

And since

Step 1: Solve the third line for

Step 2: Solve the second line for its remainder aka 5,

and then plug this into step 1.

Step 3: Solve the first line for its remainder aka 6,

Plug this into the result of step 2.

And we’re done. We’ve found a solution:

Boo! No Proof!

We won’t give a detailed proof here of Bézout’s Identity. Mostly because it relies on the Euclidean Algorithm’s quotients and remainders to find

Generalization

Bézout’s Identity has a more general form. What would happen if we tried to find a solution to the equation:

Where we still identify

But, then multiplying every term by 10 gives:

Thus,

Corollary: Let

andbe integers and. Then the equation:has an integer solution if and only if.

We did not go through a formal proof of Bézout’s Identity, nevertheless, we will use it in this proof.

Proof: (Click in the Discovery)

Proof: Let

Forward: If

For the hope of a contradiction, assume that there is a solution to

This is impossible, since if we divide the equation above by

Thus, it must be that

Backward: If

By Bézout’s Identity, we know there is a solution

We have found a solution, (

Zero or Infinite?

Ok, what’s left is there to do? We claimed at the beginning that

As we’ll see, there is either no solution or infinitely many solutions to

Theorem: Let

andbe integers and. Ifthen the equation:has infinitely many integer solutions. In the case thatthere is no solution.

Intuition: We already know why there is no solution when

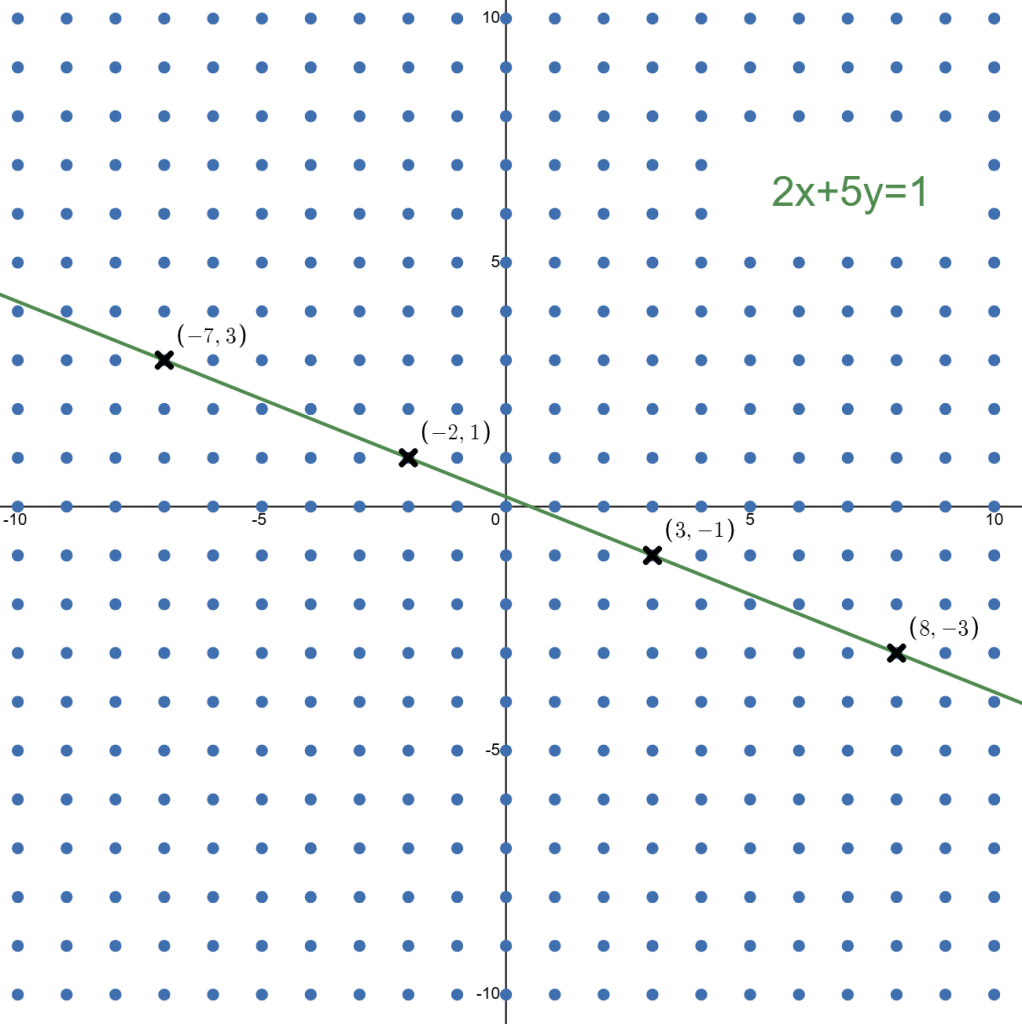

Let’s consider the examples we saw in the beginning,

Let’s graph these two equations. Observe that every grid point hit (marked with an x) by the line is an integer solution to the equation of the line! This is the key idea.

Turn your attention to the green line given by

We chose to add 5k to

Another way to see this is to add and subtract 10k to

Where we chose 10 because

The red line

Before we do the full proof, a quick lemma.

Euler’s Lemma

Here’s the idea. Take the integers 7 and 490. Since

Let’s do another one. Consider again 490, but this time instead of 7 we use 10. In this case, every factor pair does not have at least one integer that is divisible by 10 even though

What’s the difference? Take a look at the situations when we fail to have one integer that is divisible by 10, say the pair

If we can somehow guarantee that none of the factors of 10 split up or that they are all in one factor, then it must be that ten divides that factor. We do this by forcing one factor to be relatively prime with 10. Ie, if

This is known as Euler’s Lemma:

Euler’s Lemma: Let

,, andbe integers. Ifand. Then,.

Proof of Euler’s Lemma: (Click in the Discovery)

Let

Multiplying through by b, we get,

Recall that

Since

We conclude

Back to The Proof of Zero or Infinite?

Proof: (Click in the Discovery)

We’ve already took care of the second statement (when

We are going to do a constructive proof of this theorem. We will find an expression for the infinitely many solutions to the equation

Let

We already know that there is at least one set of solutions to

Recall that

This leaves the integer coefficients

Does it make sense that

Rearranging our equation above to be,

We can see that the left-hand side is divisible by

and by Euler’s Lemma:

For some integer

Plugging our solution set for

Therefore, we have the two sets of solutions:

Since

Example

With our running example,

Or, simply

Let’s check different values of

| | |

| -1 | 8 | -3 |

| 0 | 3 | -1 |

| 1 | -2 | 2 |

| 2 | -7 | 3 |

And if you check the graph from earlier, these points are there.

It’s the Final Countdown… danananahhh

*I know you sang it in your head!*

Today’s post was much longer than usual! I hope you found it fun! Oh and the standard terminology for when we are finding integer solutions an equation is to call the equation a Diophantine equation.

There are many more Diophantine equations that we know how to solve. I recommend you check some out if you found this fun!

Your Own Problems

- What are the integer solutions to

- We showed our solution set is given by

- If you restrict x and y to be greater than or equal to 0, what different numbers n can you get in:

Footnote:

Leave a reply to Newbie at Number Theory (Part Four): Primes – A Kick in the Discovery Cancel reply