Today’s part two of our dive into number theory. For those who haven’t read part one about the division algorithm click here, because we plan to use it! We talk everything Euclidiean, except for Euclidean geometry! We will learn about another algorithm which is a very useful tool to find common divisors of two integers. More than that, it can be used to find all combinations of those integers! But I’m getting ahead of myself. We start at the beginning and discuss the Euclidean Algorithm and the greatest common divisor.

Some Notation

Like any branch of mathematics, there are certain notation conventions that are used. Number theory is no different. We want a shorthand for when a number is a divisor of another number.

For example, 5 is a divisor of 15. Likewise, 24 is a divisor of 96. Another way to say these two facts is: 5 divides 15 and 24 divides 96. The way we write this shorthand is the following:

Notation: Let

andbe integers such thatfor some integer, then we saydividesAnd we write. Hence the following two are equivalent statements:

We can also say

is a multiple of.(NOTE:

are all integers)

With the numbers we were using we’d write:

and

Since

The Greatest Common Divisor

When I was in school, I would always confuse the greatest common divisor and the least common multiple. Both are important (and related to one another), but we will focus on the greatest common divisor today.1

If you remember from school, the greatest common divisor of integers

In elementary school the way I found the greatest common divisors was by listing the divisors of each number and finding the integers common to both lists. Using 30 and 42 again, I would have done the following:

Where the boxed numbers are the ones that are common between the two lists. Then I’d search for the greatest common number on the lists. In this case, it was 6. Thus, the greatest common divisor of 30 and 42 is equal to 6. Not bad…

This method is surefire; however, it’s not the best thing we can do. For example, if I gave you the numbers 1,231,872,638,162 and 9,287,391,721,397. How would you write out the factor lists? You’d need to know the prime factorization of both numbers to even start. Not good.

This is where the Euclidean Algorithm comes into play. It’s a set of steps that allow us to find the greatest common divisor of two numbers without needing to do any factorization. However, it can require a lot of steps and sometimes it would be easier to just factor, so it’s not perfect. For example, if all I needed was the greatest common divisor of 30 and 42, I would not use the Euclidean Algorithm, because factoring 30 and 42 is easy. But for numbers like 1,231,872,638,162 and 9,287,391,721,397, I would use Euclidean Algorithm because factoring these numbers is much harder to do.

The Euclidean Algorithm also has some other advantages. But let’s leave this for the section Mysterious Motivation.

Before we move on, let’s write out the definition of the greatest common divisor.

Definition: The greatest common divisor

of two integers,andis the unique integer that satisfies:

- It’s a divisor of both

and, ieand, and- For any other common divisor

where bothand, it must be.If

satisfies both criteria then we write

From before,

NOTABLE EXAMPLE: Let us consider when

The Euclidean Algorithm

This algorithm notationally is very confusing, however, actually doing it isn’t so bad once you get the hang of it. The idea is the following:

We have integers

Next, focus on the remainder

Here’s the key: We claim, that if

If that’s true, since

However, sometimes we still cannot factor

Like earlier, if

We claim, if

Like before,

We might now be able to factor

. . . and again, and again, and again, as long as the remainders are nonzero. Let’s not worry if we can factor our new smaller numbers at each step.

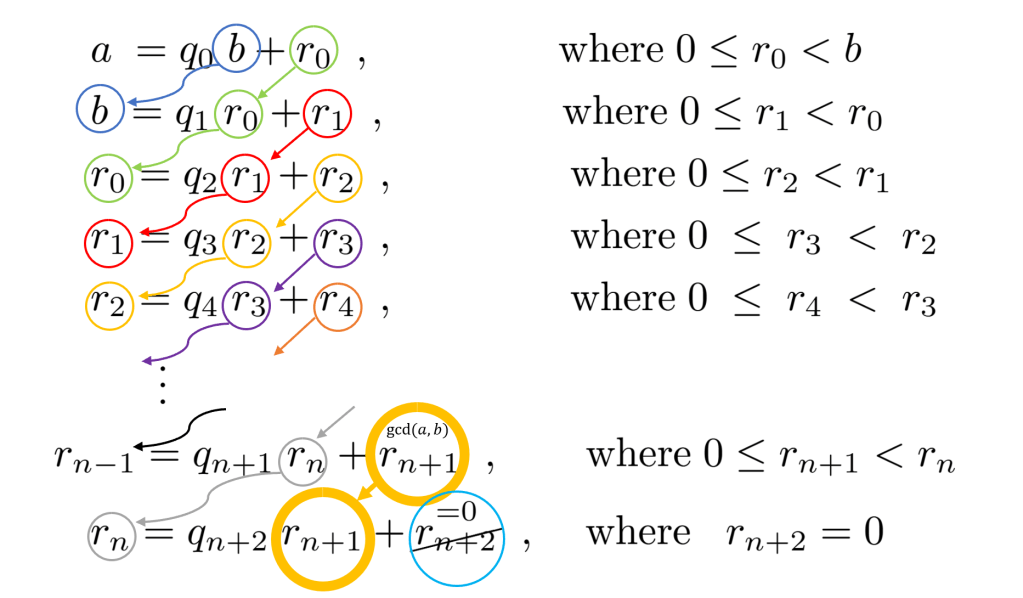

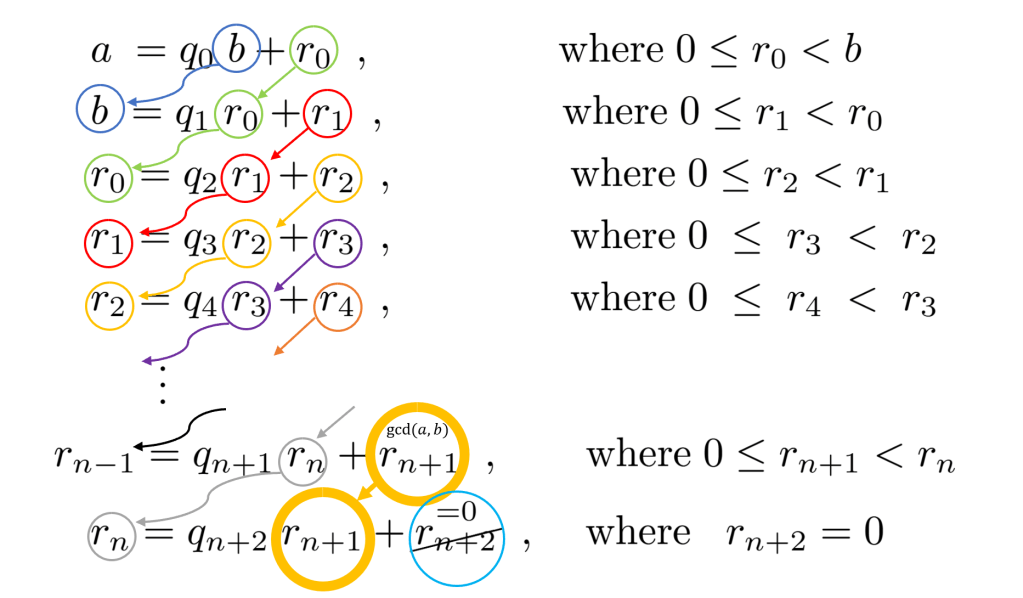

We’d end up with something like this:

We’d get some remainder

with decreasing integers: .

Since

And where done!

But did you notice that we just implicitly assumed that at some point these steps would come to an end when a remainder would equal zero, in this case

.

And since there are only finitely many integers less than

If every claim made above is true, then we’re done! We have found The greatest common divisor,

Let’s do an example and then we’ll go through the proof. But, to make the algorithm easier to follow, here is a schematic:

Where you conclude

Example 1: gcd( 59 , 301)

Remember, we progressively use the division algorithm, and the last nonzero remainder is the greatest common divisor.

Thus,

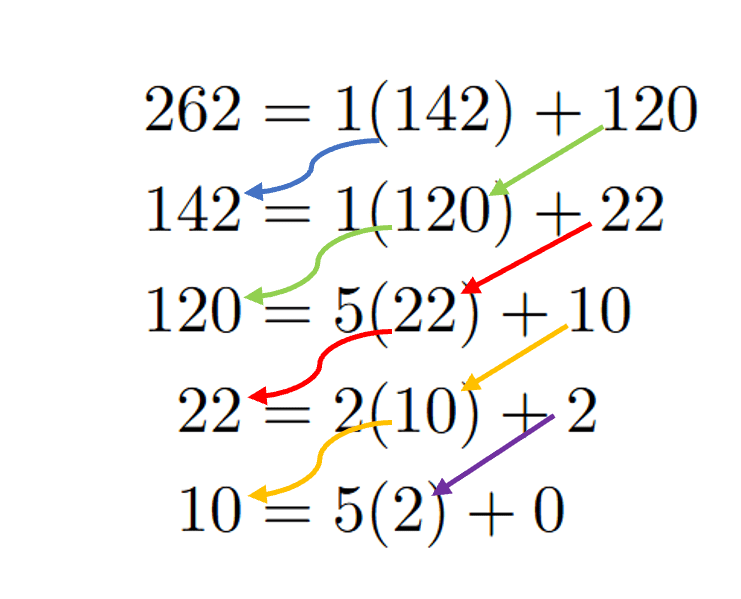

Example 2: gcd ( 142 , 262) =2

Thus

Euclidean Algorithm “Proof”

Lemma:

Let

andbe positive integers withIf.

, then.

Proof of Lemma: (Click in the Discovery)

Let

Or, the set of divisors of

Why would this imply

We know

So, if we can prove the set of divisors of

Forward: If

Consider some divisor .

Recall the division algorithm tells us there exists integers

Solving for

Using our knowledge that

Hence

Backwards: If

The proof of the backward direction is the same as the forward direction, for the most part… So, I challenge you to finish this proof!

Conclusion: Since

We now have enough to prove the next theorem!

Theorem: The Euclidean Algorithm really works…

Proof Idea: By repeatedly applying the division algorithm we end up with a chain of remainders with the property that each one is less than the previous. Since each remainder is greater than or equal to 0, this chain must come to an end because there are only finitely many integers less than

Let’s say

By applying our lemma at each step, the greatest common divisor is ‘carried along’ each step, meaning:

Where we used that

Thus,

A Motivating Mystery

Ok, so we have the Euclidean Algorithm now. We know how to use it, is it good for anything? Yes. It can be used to answer the following questions:

Let’s consider,

Are there integer solutions? Meaning are there integers

Give it a try!

I’ll wait…

Did you find any?

No?

Does that mean you didn’t try enough, or are there no solutions?

Ok, try this one:

It’s almost the same as the first.

Give it a go!

Did you find any?

Maybe x = -2 and y = 1: since

The first equation has no solutions whereas the second one has infinitely many solutions.

What’s the problem with the first equation, why are there no solutions? And what’s so nice about the second equation that allows for infinitely many solutions?

Unfortunately, this blog is tooooo long as it is. So, you’ll have to wait until next week! Try to come up with a conjecture of your own. Remember it’s all about a Kick in the Discovery!

TO BE CONTINUED…

Closing Remarks

Though you may think that the Euclidean Algorithm isn’t very useful in an age when you can just ask Wolfram Alpha to find the greatest common divisor of any two integers you want, and you’re partly right since most computations and arithmetic are no longer done by hand (unless you are taking a test and your teacher doesn’t allow calculators, in which case that stinks and I’m sorry!)4 The utility of the Euclidean Algorithm is in its application to theory. As well see next time, it has far-reaching implications.

Footnotes:

- Ok, I couldn’t help myself. Let

.

- For example,

.

- To the person who invented the number 0, thanks for nothing! ↩︎

- One mathematician says to the other, “Did you know that only 99.9% of people know some number theory? And luckily, I’m one of the 10% who do!” ↩︎

Leave a reply to Newbie Number Theory: (Part 3) ax+by=1 – A Kick in the Discovery Cancel reply