Aggravating Addition

Let’s get straight into it and try to add every counting number from 1 to 100. Basically, what is 1+2+3+…+99+100 = ???

There’s a long way and a short way to do this. Let’s be lazy and do it the short way.

We begin by sitting and thinking. After a while we notice that we can pair off numbers in the sum. Let’s pair them in the following way:

(1 with 100) (2 with 99) (3 with 98) . . . (50 with 51).

Do you notice why we might have done this particular pairing? Take a moment to look again!

Seriously, go back and look again! It’s so clever and once you see the answer you lose the chance to discover it yourself!

When you sum the two numbers in each pair, they all total 101. For example, 1+100 = 2+99 = 3+98 = … = 50+51 = 101. Can you tell how many groups of 101 we have?

Take another moment to guess!

There are 50 pairs of 101’s to add together. Thus,

Another way we can write

Pair: (1 with 52) (2 with 51) … (26 with 27)

This time we have 26 pairs that total 53.

This time we can write the total using 52 and 53 in the following way:

Ok, let’s build on the sum we started with. Our goal is to now add 1 + 2 + … + 101. We can do the same thing we have been doing, but there is an easier way that builds on what we’ve done so far. We already know 1 + 2 + … + 100 = 5,050. Therefore, 1 + 2 + … + 101 = 1 + 2 + . . . + 100 + 101 = 5,050 + 101 = 5,151. Easy!

Thus, we see that if we already added together 1 + 2 + . . . + n, we also have most of the work done for the sum 1 + 2 + . . . + n + (n+1) too.

If we try this a few more times with different n, we might begin to notice a pattern. It always seems like the total always can be written in the following form:1

Is the formula above always true? This would be useful if it were. We would never have to go through the work of pairing numbers and then finding how many pairs we made if the formula always works.

Based on our efforts so far it seems to work. Can we prove it works for all counting numbers? More technically, is this true for all n in

Proving the Problem

To set our intentions from the get-go, we want to prove:

The formula

As a disclaimer, we will be using induction. But let’s motivate why it works.

We might begin, like we did earlier, by checking some numbers

Choosing

Let’s check

Let’s do one more check with

Did you notice anything when we used the result for

In a spur of inspiration, we notice the following: If we can show

Why would we be done?

Continuing with our running example, imagine we already showed that the formula for n implies the formula for n+1 . Then, since we checked that our formula holds for n=100, it holds for n+1 = 101 too. But since we now know the formula holds for n=101 it must then hold for n + 1 = 102. But since we now know the formula holds for n = 102 it will then hold for n+1 = 103. But, since we now know the formula holds for n = 103 it will hold for n+1 = 104. And on and on and on… or to infinity and beyond!

Recall we already checked the formula worked for n =1 too. Thus, it works for n+1=2, since it worked for n=1. Now we now know it works for 2. Thus, since it works for n=2 it works for n+1=3 and so on…

Recap: we showed the formula

Now, can we show that

Let’s assume that we already checked that

.

We’re done! Since we know the formula works for n=1, and now we know this implies it works for n=2. And then this implies that it’s true for n=3, which implies n=4 etc…

But, wait you say! I thought I was going to learn about induction!

And I say, you already did!

Induction states: Let the proposition that we want to be proved be denoted P(n). If we show (i) P(1) is true and (ii) the truth of P(n) implies the truth of P(n+1), then P(n) is true for all natural numbers in

For our example, P(n) is the statement that

Interesting Inductions

Ok, I hope that was helpful motivation. If you made it this far and are more confused than ever, this next section is for you! We do some practice problems using induction.

Problem 1: Prove

Ok, here’s what we do. We check

Base Case n = 1: Just plug 1 into our expression and see if it is true:

Not so bad so far. Now we assume that

Where we used

Thus, by induction we conclude: if

Problem 2: Prove that the sum of consecutive odd numbers is always a square number.

I love this one! There is a great geometric way of thinking about this, and I encourage you to ponder it! But, for the sake of induction, we won’t do it here.

Problem: We want to show;

Base Case: Consider

Inductive Hypothesis: Assume it’s true that

Goal: Show that the inductive hypothesis implies

Indeed,

By induction we are done!

Improper Induction

No blog about induction would be finished without mentioning some pitfalls of induction. There are three main ways that people tend to mess up their induction.

- First, no one checks if the base case is correct. There are many times when you can show that P(n) implies P(n+1), where P(n) is never true in the first place.

- Sometimes you need to check more than one base case.

- Lastly, sometime the induction hypothesis doesn’t get used or it’s used incorrectly. For example, notice how we didn’t start with and then modify P(n) to get P(n+1). We started with P(n+1) and then found a way to use P(n). It’s a subtle and important difference.

There are many, many great resources out there that show false inductions some great examples are found at Brilliant.org if you’re interested. To get a taste, here’s a variation on one classic:

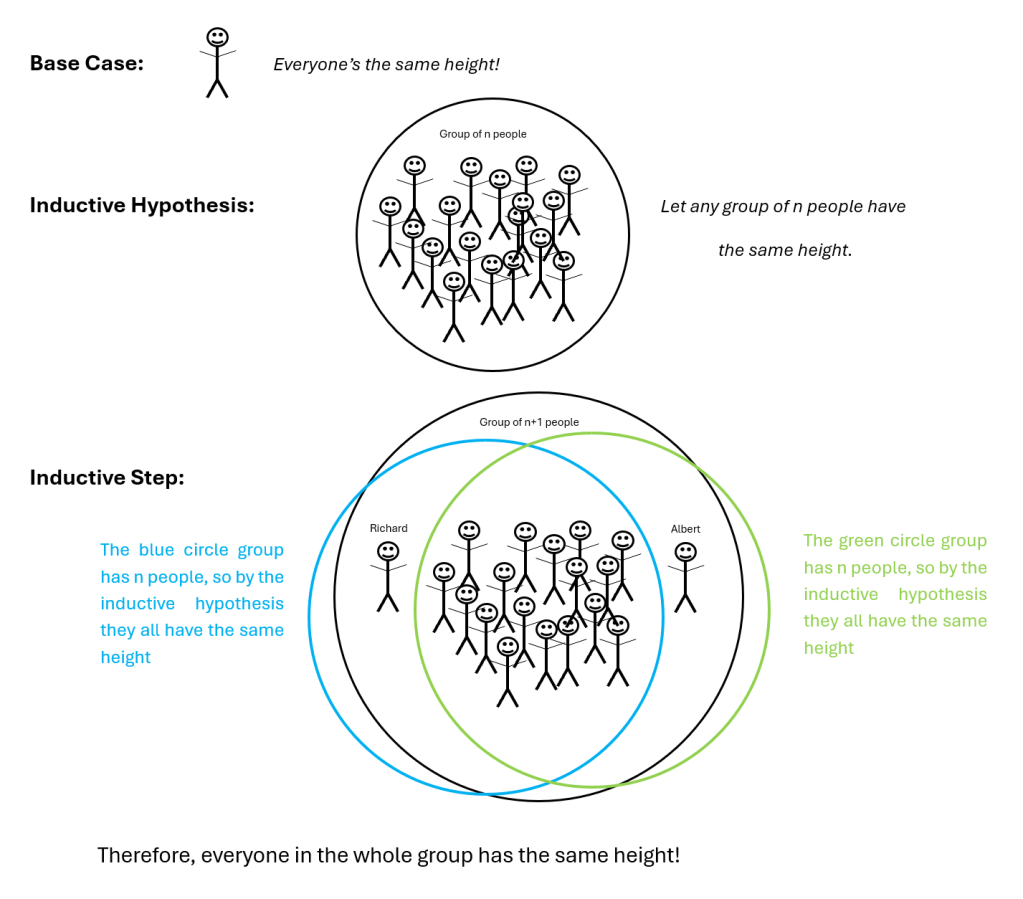

We will ‘prove’ that everyone is the same height.

Base Case: For any group of one person everyone in the group is the same height.

Inductive Hypothesis: Assume that for any group of n people they are all the same height.

Goal: Use the Inductive Hypothesis to show that any group of n+1 people are all the same height.

Indeed, since for any group of n+1 people, we can take one person out, call them Richard. Then we have a group of n people, and by our Inductive Hypothesis everyone has the same height. Now, let Richard back into the group and take out another person named Albert. We again, have a group of n people. So, by our Inductive Hypothesis everyone has the same height. Now bring everyone back together. Since everyone had the same height in those two subsets of people, the whole group has the same height!

Clearly, this is false. But why?

Take a moment to look back at the ‘proof’. You got it!

The problem is in the inductive step. It fails for n+1 = 2. Call the two people in the group Richard and Albert still. We can take Richard out still. Then it’s true that everyone left in this group of n=1 (only Albert) has the same height. Bring Richard back and take out Albert. The same thing happens. Everyone in this group of n=1 (only Richard) has the same height. But here’s the issue, when we bring them together, we have no reason why they should have the same height! It’s possible that Richard and Albert have different heights. Our base case only told us any group of n=1 people will have the same height, not any group of n=2 people. If, however, our base case’s conclusion was any group of two people have the same height, then it would be true that everyone would have the same height.

Closing Remarks

Induction is an incredible tool, however, to use it you must be careful. I hope this blog helped you understand how to apply it to any situation you need.

Footnote:

- By the way, the eagle-eyed problem solver might notice that when we add to an odd number, for example 21, our pattern changes. We still pair 1 with 21 and then 2 with 20, etc to total 22. What changes is that the number 11 does not have a number to pair with! Oh no! Are we wrong? Luckily no. What happens is the following pairing,

Leave a comment