Let’s begin with an interesting problem. (I guess you can judge whether or not it’s interesting!)

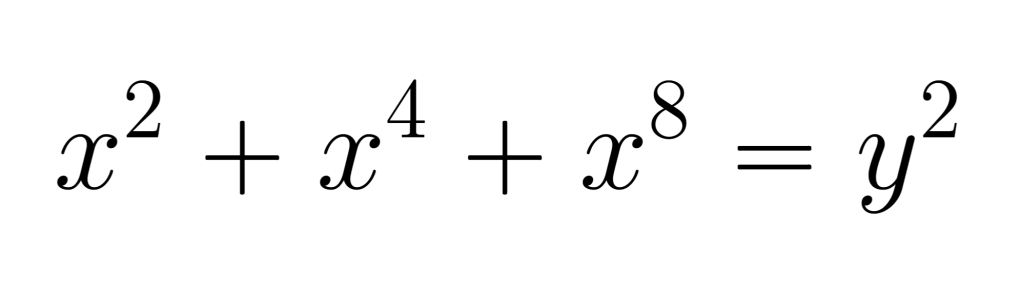

Find three squares, each with rational side lengths, whose areas add to a bigger square such that the side length of the second square equals the area of the first square and the side length of the third square equals the area of the second square? Or, using modern algebra: solve the following equation

where and

are rational numbers.

Give it a ago! It’s quite a challenge.

A Solution

This is a problem given in Diophantus Arithmetica, the book that Fermat was reading and adding comments into its margin. We will be solving this problem using modern tools, and not the way in which Diophantus solved it. We will be relying heavily on modular arithmetic, so if you need a little refresher take a look at this article.

The key idea is the following: If we found a solution to the problem, then our solution should carry over into a world, where p is prime and n is a positive integer. With this as our motivation, we will begin by trying to find solutions to

working

.

Mod 3 Solution

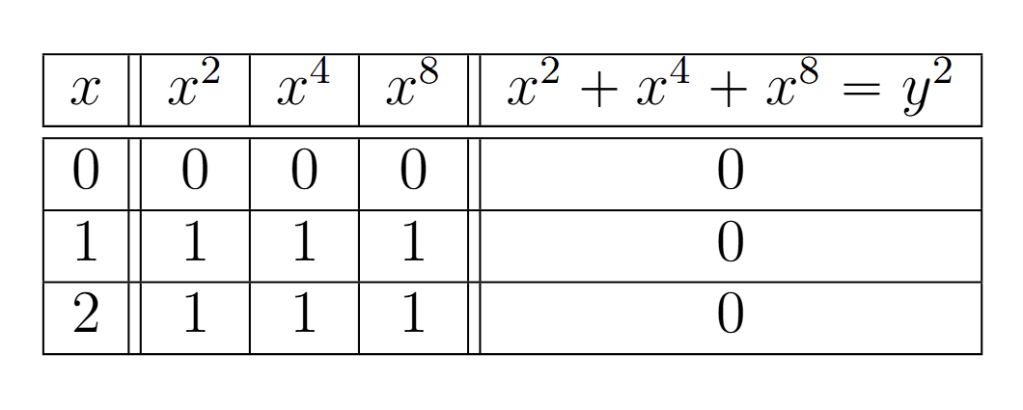

Working is advantageous because we can more easily search for a solution since there are only finitely many (three of them) modulo classes

. Meaning we only need to check the cases where

and

Let’s construct a table to more easily see what is happening:

Note that our solution requires that Furthermore, we have three solutions:

but let’s ignore

because we don’t want to count squares with zero area as a solution. Let’s choose

to work with, since it’s mildly easier to do arithmetic with 1 rather than 2! In other words, our

solution is given by

and

Mod 9 Solution

Let’s carry over our solution , to

or

This means that our solution will be of the form

and

It follows that

Thus,

and Combining everything, we see that

must satisfy the following,

from which we deduce

To summarize what we just found, we now have

and

Mod 27 Solution

This isn’t our first rodeo, so now we know we set and

From these we determine the following,

Hence,

And we also have Therefore, we deduce,

and thus, Altogeher,

and

Mod 81, 273, 819, . . . Solutions

We will not carry out all the arithmetic; we will just say that we could deduce that at every step we will end up with and

Bringing it Together!

We have deduced (kind of) that a solution to our problem is the following geometric series

Can we make sense of this ridiculous answer? We have equal to a divergent geometric series (the sum blows to infinity), this is nonsense! With reckless abandon, we use the formula we’d use when considering convergent geometric series:

Note, this should only apply when

and since we have

we are breaking all the calculus rules that we learn! But if we continue, we find

Again, ridiculous! However, we’re mathematical rebels so we use this as our solution. It follows,

Substituting back into our original equation gives,

Wait just a gosh darn minute! Take a look, So we just found a solution

I think this is quite a victory…

What Just Happened?

We just used a technique called Hensel lifting. We took a solution and used it (lifted it) to find a solution

. Then we lifted the solution

to find a solution

. This led us to a divergent geometric series, which should have been nonsense and shouldn’t have given us anything. And yet… it gave us a solution…

The reason why delves deep into the realm of a new number system called the p-adics. In this new number system, we define the distance between two numbers in a way that we are not used to. Usually, we’d say that the distance between and

is equal to their (positive) difference:

However, when working with the p-adics we get something different. Let’s use the prime 3 again. The 3-adic distance between

and

is equal to

. This is because we now define distances using the following rules. First, we set up what’s called a norm. You can think of this like a generalized absolute value.

P-adic Norm: Fix some prime number

For any rational number

(where

and

) pull out as many factors of

as you can. This means that we have

where

and

and

Then the p-adic norm is equal to

For example, let and we’ll consider

Then we can pull out two powers of 3 from the denominator,

so that

Now we define the distance between two numbers using the norm:

P-adic Distance: Fix some prime number

For any two rational numbers

and

the p-adic distance is defined to be

Going back to our previous example, we can now see that , which we just saw was equal to 9.

Now you could ask, does this notation of distance even make sense to consider? Well, yes, since this notation of distance satisfies properties that we want a distance to satisfy, which we will not go into right now (if you’re interested, just search for ‘definition of a metric’ or you can go here: Metric Space | Brilliant Math & Science Wiki). We might also say that this notion, although unfamiliar, is helpful since it allows us to make sense of things like

Being Creative

First, I want to mention that I heard this problem and solution from two sources, the first is the following Veritassium video: What if you just keep squaring?, and in the first lecture of the great mathematician Alex Kontorovich’s lecture series: Automorphic Representations and L-functions.

Second, I think this is a great lesson in how creativity plays a crucial role in mathematics. Not many people get to see this side of it, and that’s a shame. However, once you discover something astounding (like how our series diverged and gave us a solution) the game has just begun! The next step is to make sense of, make rigorous, and further develop what we did in order to solve this problem.

With this said, see you next time!

Be Kind. Be Curious. Be Compassionate. Be Creative.

And Have Fun!

Leave a comment