There are different sizes of infinity. I know, that is a surprising (and amazing) fact that needs to be justified (or proved)! As you may know, there are an infinite number of natural numbers and there are an infinite number of real numbers

However, what you may or may not know is that the infinity of real numbers is vastly larger than the infinity of the natural numbers!

There are many great sources out there that explain the intuition behind this strange result regarding infinity which I linked below:

- How An Infinite Hotel Ran Out Of Room – Veritassium

- Real Analysis: A Long-Form Mathematics Textbook by Jay Cummings

- Real Analysis, Lecture 7: Countable and Uncountable Sets – Professor Su’s Real Analysis Lecture Series

- Infinity is bigger than you think – Numberphile

- An infinite number of $1 bills and an infinite number of $20 bills would be worth the same – Stand Up Maths

- S01.9 Proof That a Set of Real Numbers is Uncountable – MIT’s OCW

- Lecture 2: Cantor’s Theory of Cardinality (Size) – MTI’s OCW

Most of the time, when we are taught a proof of this fact, that the cardinality (size) of the real numbers is larger than the cardinality of the natural numbers, it is Cantor’s Diagonalization proof. Today, we will go over a different proof! One that relies on the least upper bound property of the real numbers!

What Does it Mean to be Countable?

First, let’s set up some concepts and terminology.

What are we doing when we count a group of objects? We are matching one natural number to one object, this is why the natural numbers are sometimes called counting numbers. We all know that if we want an accurate count of how many objects we have, we must make sure that we don’t miss any objects and we need to make sure we don’t over count any objects. To be more mathematical, suppose there were objects. We’d then say there is a bijection between the set

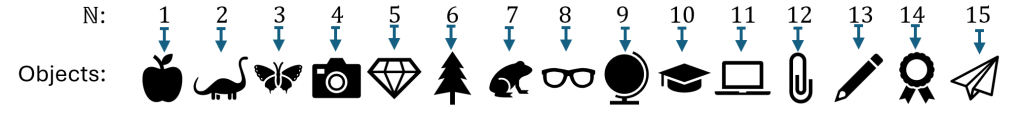

and the set of objects. A bijection is the fancy math way of saying there is a one-to-one correspondence between the two sets, that is every natural number gets a unique object, and every object gets a unique natural number. For example, when we have fifteen objects, we can count them as follows:

Where we attached one and only one natural number to each object (e.g., 3 got mapped to the butterfly).

In the case we have an infinite number of objects, like the set of integers , we can use the same principle! I think we can both agree that there are an infinite number of natural numbers and an infinite number of integers. What’s less obvious is that the infinity of the natural numbers is the same size as the infinity of the integers! This is surprising since it seems like there are more integers than natural numbers; however, this isn’t the case! The reason why the two infinities are indeed the same is because we can count the integers using the natural numbers just like we did with a finite list of objects using a bijection. The easiest way to see the bijection is by listing out the integers (like how we put the objects in a row/list) as illustrated below,

Where we can now count, using natural numbers, the integers one at a time.

Another surprising result is that the cardinality of the rational numbers (set of all integer fractions) is the same as the cardinality of the natural numbers! This should be even more surprising since there is an infinite number of fractions between any two natural numbers! For example, between 1 and 2 we have And yet the two sizes of infinities are the same! But, to show this, we need to find a way to list, or count, the rational numbers.

The basic idea is to write rational numbers in a grid:

By zigzagging though this grid we will hit every positive rational number. The only thing that we need to be careful of is double counting rationals like . We do this simply by skipping the rational numbers that are not in simplest form.

We’ve seen a couple of examples of infinities that are the same size as the infinity of the natural numbers. When a set is the same size of infinity as the natural numbers, we say that

is countable. How have we demonstrated that this is the case for the integers and rational numbers? We’ve shown the set

is countable by finding a one-to-one correspondence between the natural numbers and the set

Definition (Countable): A set

is called countable if there is a bijection (one-to-one correspondence) from the natural numbers

to the set

When this happens, we write,

Where

is used to denote: the cardinality (size) of the set

Another way of thinking about a set being countable is to think of the set as being listable. We’ve been using this method of thinking the whole time, take the example of the integers: We were able to list them in the order

which showed that we can match each integer to a natural number with a one-to-one correspondence. Likewise, the grid of fractions showed us a way to list the rational numbers:

We can summarize everything we have discussed thus far in the following,

Or, in words: the integers and rational numbers are countable.

There are a lot of Real Numbers

It seems like every infinite set is the same size, in the sense of countability. However, as we will see soon, the size of the set of real numbers is a larger than the size of the natural numbers. Actually, much much larger! But to prove this fact, we will need a quick theorem regarding non-empty nested closed intervals of real numbers.

Theorem (Non-Empty Nested Closed Intervals): Let

be a non-empty closed interval of real numbers with the property that

for all

(that is, we are nesting each of interval,

,in the previous interval,

). Then, the intersection of all the intervals

is non-empty:

In symbols,

Proof: (Click in the Discovery)

The proof relies on the least upper bound property of the real numbers.

Observe that the condition is equivalent to the condition,

Consider the sequence

First, we note that

is monotone increasing and bounded by

By the monotone convergence theorem (which relies on the least upper bound property) we know that

converges to

Furthermore, every

is an upper bound for every

And so by definition of a supremum we have

for all

Hence, we have

for all

It follows that,

proving that

Now we are ready!

Theorem: The cardinality of the natural numbers is less than the cardinality of the real numbers.

Proof: (Click in the Discovery)

Assume for the hope of a contradiction that the real numbers were countable. This means that we can list the real numbers in the following manner:

We will construct a set of nested closed intervals that will lead to a contradiction.

First, construct a closed interval so that

and

.

Next, construct another closed interval so that way

and

and

Note this means that both

and

are not in

Guess what? Now construct yet another closed interval so that

and

and

.

Keep doing this for all That is, construct a closed interval

so that

and

and

.

Note that for all

(or for all

) by construction. It follows that

is empty. However, we have non-empty nested closed intervals whose intersection, which by Theorem (Non-Empty Nested Closed Intervals), should be non-empty. This is our contradiction. We conclude that we cannot list the real numbers, that the real numbers are not countable, and thus a larger infinity than the natural numbers.

How clever is that?

But to be more rigorous, technically we have only showed that not that

To show this last step we need to understand when one set has less elements than another.

Imagine a youngster learning how to count. So far, they only know how to count to 10. This means that they will not be able to count the group of fifteen objects, since their set of counting numbers is too small. An equivalent way to say this is that the youngster can still count the first ten object using a one-to-one correspondence, but there will be objects left over that get missed. The math way of saying this is, there is an injection from the set

to the set of fifteen objects.

Taken altogether, we have,

Definition (

and

): Let

and

be two sets. We say that

if there is an injection from

to

***Note, when we have both

and

it must be

***

To finish the proof, all we need to do is find an injective way to count. That is, we want a method to counting real numbers using the natural numbers which leaves left over and uncounted real numbers. Like the youngster trying to count fifteen blocks with only the numbers 1, 2, 3, … , 10. The easiest way to do this is to count some of the real numbers by matching the natural number 1 with the real number 1, and the natural number 2 with the real number 2, etc. This leaves lots of real numbers left over, hence, But, in our earlier proof we showed that

Thus,

Closing Remarks

This proof is wonderful for a number of reasons. First, it’s different than the standard proof that we all learn, so it’s nice to mix it up a little. Second, because I could use my favorite theorem from elementary analysis: the monotone convergence theorem (yet again)! I hope you had some fun, and I look forward to “seeing” you next time!

I would like to thank Professor Francis Su and Harvey Mudd College for putting out their real analysis lecture series, where I learned this proof (in the following lecture).

Be Kind. Be Curious. Be Compassionate. Be Creative.

And Have Fun!

Leave a comment