We’ve asked and answered the question, “Can we ever prove that a sequence must converge without needing to know or find its limit beforehand?” in Let’s Get Real… Analysis (Part 5): The Monotone Convergence Theorem. Today, we will be proving something that has a similar flavor to that.

When I first saw what and

were, I found them very tricky to parse. I hope today’s article will help you if you feel the same way!

What are  and

and  ? (haha tiny math writing)

? (haha tiny math writing)

There’s no motivating this; here are the definitions:

Definition (Limit Superior): Let

be a bounded sequence and define the sequence

by

. If the limit exists, define

Similarly, define the limit inferior:

Definition (Limit Inferior): Let

be a bounded sequence and define the sequence

by

. If the limit exists, define

***Note we may abbreviate these by

and

.***

These definitions are tricky to parse the first few (hundred) times you read them. Let’s go through some examples to try to help out!

Oh, and for some reason when I think of limSUPs I want to listen to the superman soundtrack… not sure why??? But in any case, here is the original Christopher Reeve Superman Theme and the new David Corenswet Superman Theme. Enjoy! Oh and my favorite superhero is Captain America!1

Graphical Example

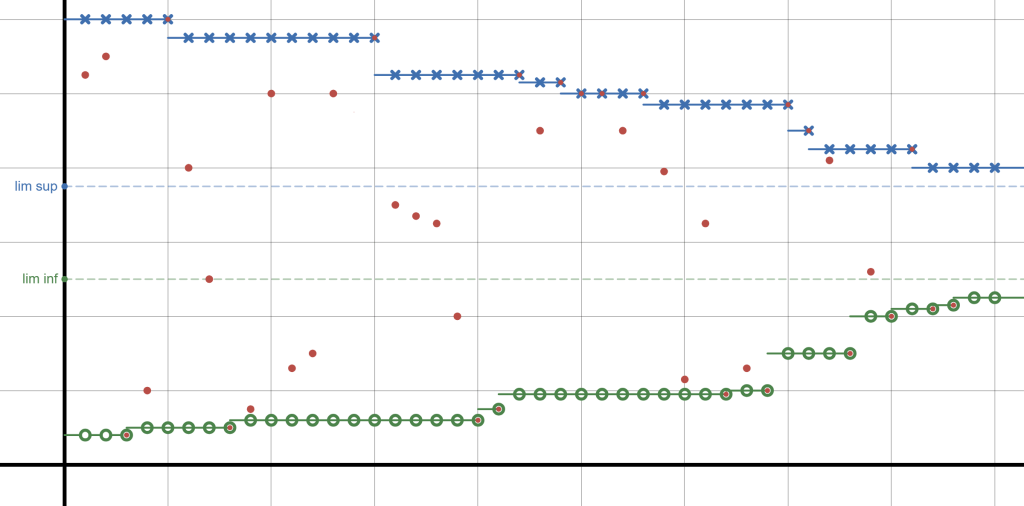

For our first example, take a look at the following graph. The red dots are the elements of the sequence plotted against their index; that is, for the sequence , we plot

in red. The blue

s represent the supremum elements

. Similarly, the green

s represent the infimum elements

.

For example, the first five elements . Similarly, the first three

.

Take a few moments to understand what the picture is showing and then move on.

Once you find and

, you can then take their limits as

. That’s all there is to it! Let’s work through some examples together to make sure we understand what’s happening!

Example 1:

Consider the bounded sequence and observe that,

Which we can prove by noting that and

for all

. Thus,

and by our theorem Proving Supremum Analytically (PSA for short) (or see footnote2) we are done!

Continuing on to we have,

which we have proved before here.

Finding is even easier since,

Which we can prove by noting that is a lower bound of the set

and that for any

there is a

such that

by the Archimedean property. Therefore

for all

and thus,

Let’s try another sequence!

Example 2:

Consider the bounded sequence . Observe that,

I leave it for you to prove as a challenge (you’re welcome)! Continuing on to we have

Which is again, left as a challenge!

Turning our attention to we deduce that

I leave it for you to prove as a challenge (again, you’re welcome)! Continuing on to we have

Which is again, left as a challenge!

Conjecture Time!

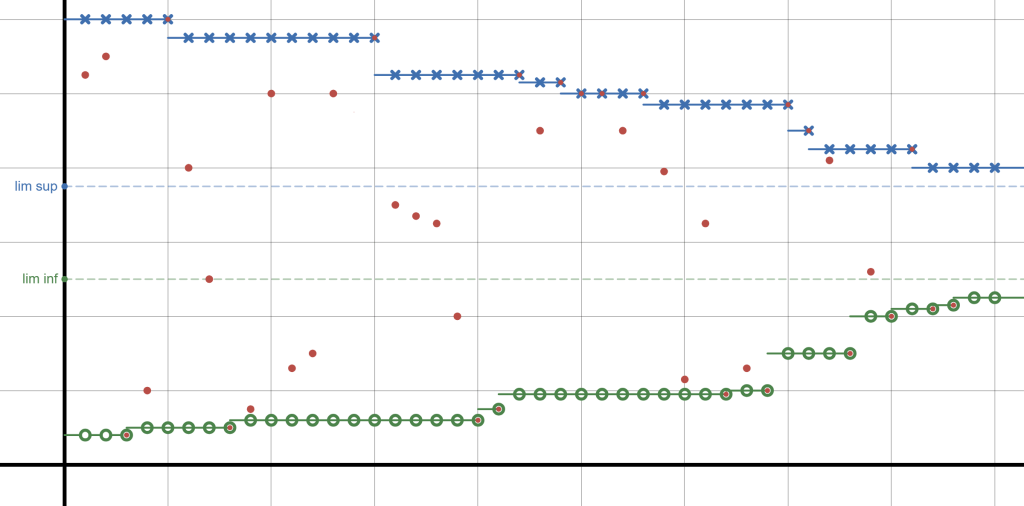

Take another look at the plot earlier; here it is again for convenience

What do you notice about the blue sequence ? What do you notice about the green sequence

? You might notice that

is a monotone decreasing sequence and

is a monotone increasing sequence. Recall, monotone increasing (or decreasing) means that

(or

) for all

. Oh oh oh! Do you recall my favorite theorem from real analysis? The monotone convergence theorem states:

The Monotone Convergence Theorem (increasing case):

If you have a monotone increasing sequence

i.e., then

- when

is unbounded above the limit diverges to infinity, or- when

is bounded above the limit exists and is finite:

The Monotone Convergence Theorem (decreasing case):

If you have a monotone decreasing sequence

i.e., then

- when

is unbounded below the limit diverges to negative infinity, or- when

is bounded below the limit exists and is finite:

So if and

were bounded, we could use the monotone convergence theorem to say something regarding

and

.

One last thing that we might notice is that for all

. You probably saw this without a second thought since we already know that the infimum of a set is a lower bound and the supremum is an upper bound.

Everything we observed is generally true, as summarized in the following theorem.

Theorem (LimSup and LimInf Properties): Let

be a bounded sequence and define the sequences

and

by

and

respectively. Then we have the following:

- The sequence

is a monotone decreasing sequence, bounded, converges, and

.

- The sequence

is a monotone increasing sequence, bounded, converges, and

.

- Lastly, we have the inequality

.

Proof: (Click in the Discovery)

Let be a bounded sequence and define the sequences

and

by

and

respectively.

(i) First, let’s prove that is monotone decreasing. By definition,

and

. Observe that

. This means

and hence

.

By assumption is bounded and hence

exists. Can you see why this implies that

is also bounded below?

(ii) Using part (i) and, guess what, the monotone convergence theorem .

(iii) and (iv) Use a very similar argument to parts (i) and (ii).

(v) Note that for all

. Then, by our limit laws number 2, we have

.

Not too shabby so far! Good job keeping up with this stuff; it can be really tricky. Take a moment to pat yourself on the back, and when you are ready, we have one more theorem to prove.

Subsequences of

It might seem like there is no connection between ,

, and subsequences of

. Since we’ve already seen in one of our examples

for all

is not a subsequences of

. However, there is a subsequence of

that converges to

‘s limit

! Likewise, there is a subsequence of

that converges to

! How awesome and surprising is that?

Theorem (LimSup Subsequence and LimInf Subsequence ): Let

be a bounded sequence. Then there exists a subsequence

such that

Likewise, there exists a subsequence

such that

Scratch Work: We want to show that there exist such subsequences of , and to do so, we will construct them using what we already know regarding limits, supremum, infimum, limsup, and liminf. Although you should have the opportunity to work out some of the proof on your own, we will only complete the limsup part together.

Let’s set up our conventional notation, let and let

, that is

. Using this notation, we want to find some

such that

.

Let’s take stock of what we know about . Since, we know that for any

there exists some

such that

Moreover, since is a supremum, we have the stronger statement:

Furthermore, since the above inequality holds for any , we can make

smaller for each

. By doing so we have

and

. Together with the inequality above, it seems like a setup to use the squeeze theorem. All we need to do is define the proper subsequence to be squeezed between

and

.

So, so we want and

for all

. The simplest sequence I can think of is

. By PSA for

and we know there is some

such that,

Then, for there is some

such that,

Likewise for there is some

such that,

And so on and so forth. This is the key idea to the following proof. We do change the definition slightly, but for reasons only for convince in defining .

Proof of limsup case: (Click in the Discovery)

We will construct a subsequence with the desired limit. We will define inductively as follows: First define the sequence

. We already know that

and that

for all

.

Let , so that

, and consider

. We know by PSA there is some

such that

Now assume that have all been defined in a similar way as

. We define

inductively as follows: for

there is some

, by PSA, such that,

Using this inductive definition, we note that and we can clearly see that for all

we have,

It follows from our work with subsequences that implies

. Therefore, by the squeeze theorem

as

.

Great working with you—until next time!

Limsups and liminfs are, in my opinion, very strange concepts upon first glance, but like many other topics in analysis (and math(s)) it is turns out to be very useful! Which is why it is covered in a course on analysis in the first place! Once thing that is amazing regarding the last theorem regarding limsups and liminfs is that it comes with a famous name. It’s called The Bolzano-Weierstrass Theorem:

The Bolzano-Weierstrass Theorem: Every bounded sequence

has a convergent subsequence

Proof: (Click in the Discovery)

Since is bounded we know that

Furthermore, by Theorem (LimSup and LimInf Properties) and Theorem (LimSup Subsequence and LimInf Subsequence ) there is a subseqeunce of

, denoted

that converges to

.

My all-time favorite proof is the proof of the Bolzano-Weierstrass Theorem given in “Real Analysis: A Long-Form” by Jay Cummings. Highly highly recommend this book. I cannot recommend it enough. I provide a brief description of the book in the “Resources Worthy of Study” tab.

Good job today! You made it to the end, and you should be proud! Today we covered some advanced and challenging topics, and we made it to the end. I hope that yo uhad dun and learned alittle math along the way! Until next time!

Be Kind. Be Curious. Be Compassionate. Be Creative.

And Have Fun!

Footnotes:

- Here’s the Avengers theme for you hard core Marvel fans: The Avengers. ↩︎

- Theorem: (Proving Supremum using Analysis) Let

(i)

(ii) for any

Leave a comment