Question: What Happens When You Add Infinitely Many Numbers Together???

I’ve heard that when you ask people this question, their answer tends to be something like, “Well, you get infinity!” However, this is not always the case! For instance, you can add infinitely many 0’s together (0 + 0 + 0 + 0 + 0 + … ) to get a grand total of 0. But I’m sure that they were interpreting the question as: what happens when you add infinitely many non-zero numbers together.

I’d also expect them to justify their answer of infinity, by giving an example sum such as: 1 + 1 + 1 + … which tends towards infinity.

But I want to show you that there are instances where you add infinitely many numbers (that are not zero and positive) and obtain finite answers. Today, we will demonstrate how to sum infinitely many numbers in three different ways. One is intuitive and geometric, another we use some algebra tricks, and the final way is rigorous and methodical.

Oh! By the way, if you read to the end, there is a compelling open question for you to ponder (solve)!

Infinite Inquiry

What do you get when you add together every number of the form

Let’s do some experimental mathematics! Let’s just add some of them together to see what we get, but I want to give you a chance to try it out first! Once you have tried it, click the box below!

Some experimental mathematics results!

******

It seems like the total is approaching 2. See if you can figure out why!

We claim that the sum does not diverge towards infinity, but rather the sum actually stabilizes and will forever approach a finite value. In this sense, we say that the sum converges.

***A Helpful Observation***

A helpful observation to make before we begin, is that each successive term that we are adding is half of the previous term. For instance, when we add our next term is half of one-fourth, that is

Geometric Genius!

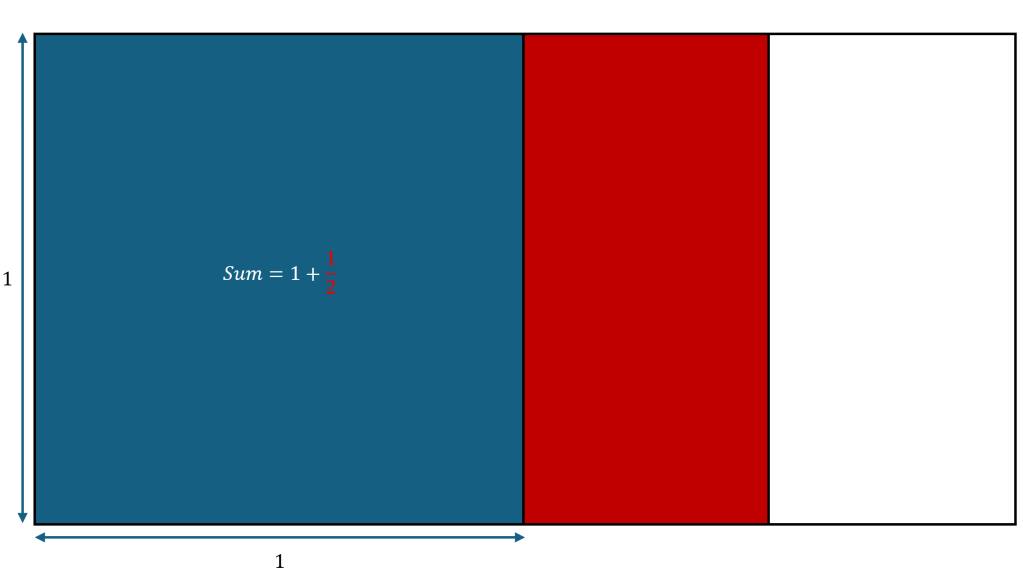

Our first geometric strategy is to interpret each term in our sum as an area of a rectangle. For example, our first term—which is a 1— is to be interpreted as the area of a square. Let’s draw this square and shade it in.

Sum = Area of Shaded Region = 1.

Now, we will cut this square in half. This is done by cutting one of its side lengths in half making a rectangle with size The area of this rectangle is equal to our second term

This is because of our helpful observation. By cutting the area of our original square in half, we get an area equal to our second term!

We will put this new rectangle in the open white space next to the square. Notice how one side of the rectangle perfectly lies along one side of the square. This is a result of the fact that we cut only one side of the square in half to get the rectangle.

Now our Sum = Colored Area = .

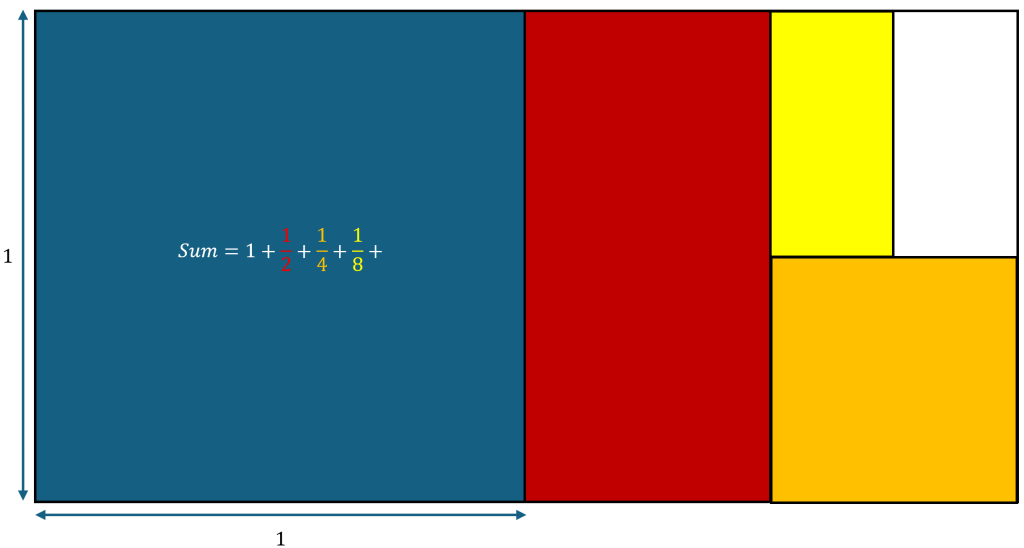

In a similar manner to before, we want to cut the area of the red rectangle in half. But now we have two shapes that we can get: either a square or a

rectangle. We choose the first option because we want our new shape to take up half of the white space left. As it turns out, we will end up alternating between cutting our width and our height in half.

Now we have a square with an area equal to our third term,

, in the sum. Since the base of the red rectangle and the new smaller square have a length of

, we can fit the new square snuggly in the white open space again.

Now our Sum = Colored Area = .

Next, by cutting the width of the orange square in half we get a rectangle. Which has an area equal to

which is our third term in the sum, and which nicely fits in the white space yet again!

Now our Sum = Colored Area = .

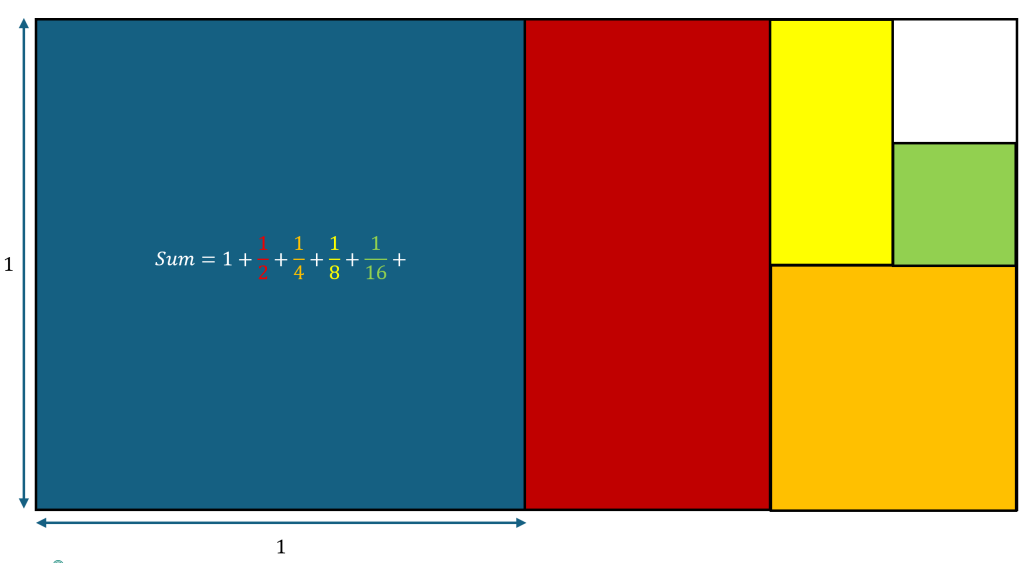

By continuing to alternate between cutting our width and height in half we get the following series of figures:

Do you notice anything interesting?

Keep looking!

The first thing that I notice is that the new square/rectangle always fits in the empty white space, due to the fact that each new shape is half the size of the remaining white area. This leads to the second thing that I notice, the shapes area won’t exceed the area of the two squares. Lastly, the shapes seem to, in the limit, fill in the white square. All together, we intuit that the total area equals 2, or

Since the colored areas will end up completely covering the rectangle!

You’ve got to love whenever you can use geometry to do calculus!

Algebra Awesomeness!

Let’s play around with our sum. It’s always helpful to give names and symbols to things that we are interested in. So, let’s first denote our sum using the letter .

Now let’s do something that might seem out of left field, multiply by one-half,

Notice anything? What about how the right-hand of has all the same terms as

, except that

is missing the first 1. Thus,

Which we can use to solve for ,

Thus, getting our sum of 2 again!

Mind-Blowing Monotone Convergence

I wanted to put a rigorous proof for this infinite series. At first, I was going to use the definition of a sequence limit; however, I chose to use one of my favorite theorems from real analysis: the monotone convergence theorem. In order to use this theorem, we will define the sequence to be the partial sums,

Our task reduces to showing two things: (1) is monotone and (2)

is bounded.

(1) Monotone: We will show that

The fastest way to see this is the case is to note that we have: Since

we have

(2) Bounded: We will show that for all

We can use the same algebra as earlier to deduce that,

.

Clearly, for all

We are now set up to use the monotone convergence theorem to conclude that converges. In the words of Ron Stoppable, Boo-Yah!

Since we know that converges, we also know that

converges to the same limit. A simple statement that will make our lives easier. Why, you ask? Take a look of what we have so far, we have

The later statement also implies

. So, we have

Adding these together gives,

Since we know that and

converge to the same limit let’s denote this limit

Therefore, we have,

Which can be solved to prove that

If we had a nickel for every time our infinite series summed to 2, we’d have three nickels! Which is not a lot, but it’s weird that we could do it three ways, right?

The Geometric Series

The sum that we were focusing on today is a special case of what is known as the geometric series. As you might have guessed, the sum gets its name from the fact that there is an intuitive way to translate our sum to a set of areas that we can draw. In general, a geometric series is an infinite series of the form,

,

where . Since this sum is nicely behaved we could prove the following result:

Theorem: (The Geometric Series) If , then

,

I’ll leave the proof to you! If you use the same logic that we used in the Awesome Algebra section, you can derive the formula really quickly. However, if you are interested in a more rigorous proof, then you must use the partial sum method that we used in the Mind-Blowing Monotone Convergence section.

An Open Problem

I want to leave you with an open, unsolved math problem! This one is sooo much fun to think about! Consider the series,

,

The easiest way to determine the sum is to observe the following series of algebra tricks:

Great! We have shown,

Now we will do what we did first, we interpret our result as follows:

Now the question is, can you find a way to tile a square with rectangles of the form

Basically, can you find a way to do this particular sum using a geometric method like the first one we covered. The algebra seems to imply that it might be possible, however, no one has found a tiling yet! Your mission, should you choose to accept it, is to find a tiling or prove that one does not exist.

Let me know what you come up with in the comments! I hope you get a kick in the discovery while solving this problem! As always,

Be Kind. Be Curious. Be Compassionate. Be Creative.

And Have Fun!

Leave a comment