Note that I’m assuming the reader has a little familiarity with groups. All that is needed is the definition of groups (which we will review) and either know some basic examples or have the ability to prove the examples given are groups.

Where to begin?

First, let’s review the definition of a group:

Definition: (Group) A set G along with a binary operation is called a group if the following properties hold: (note (B0) is what it means for

to be a binary operation.)

(B0). The operation maps every pair

to a unique element

.

(G1). The operation is associative:

for all

,

(G2). There is an identity element , where

, and

(G3). For every , there is an element

, called the inverse of

, such that

.

We denote this group by . Or, when the operation is known, we denote the group simply by

.

By going through some of the following group examples we can motivate where the concept of an isomorphism comes from.

Groups of Real and Complex Numbers

Consider the set of real numbers along with addition. These together form the additive group of real numbers:

; however, we will abbreviate the group by

. You can check that all the axioms are satisfied.

We can also use multiplication instead of addition to form a group. But since we want every element (number) in our group to have an inverse we will exclude the number 0. If we denote the set of nonzero real numbers by , then we have formed the multiplicative group of real numbers:

. Again, we will use the shorthand

to denote this group.

Everything we just discussed using the real numbers we could have said using the complex numbers instead of the real numbers. If we do, then we’d have formed the additive group of complex numbers, denoted

, and the multiplicative group of non-zero complex numbers denoted

.

Using Modular Arithmetic

Take the set of integers and addition modulo

as our binary operation. Together these form the additive group of integers modulo n, denoted by

. Question: For those who are familiar with modular arithmetic, can you show that this

is indeed a group? And for those have not yet had the opportunity to learn modular arithmetic yet, there are three options for you to choose from.

Option 1: Check out the Newbie as Number Theory series and become a number theorist in training.

Option 2: Just read on with wreck lace abandon. Aka, not care!

Option 3: Read this footnote, which contains the gist of what you need to know.1

We can also form a group using modular multiplication; however, we must be cautious. Since we need every non-zero number to have a multiplicative inverse, we must need to have be a prime number.2 We will denote this group

.

***Technically this isn’t the full story. We could just define our set to be the subset of

where all the elements in

have a multiplicative inverse modulo n.

For those who are in the know, our set would end up being

This is a result you’ll learn in number theory, but to make it easy we usually focus on when is prime.***

Permutation Groups

Yet another example can be found in the article on permutation groups from two weeks ago. I would highly recommend checking this article out if you are unfamiliar with permutation groups because one of the deepest results that we will prove using isomorphisms is Cayley’s theorem. And Cayley’s theorem is the formal connection between ALL groups and the group of permutations.

However, time is valuable, so the gist is this: You are given some finite list of numbers (or objects that you’ve assignment numbers too) and you shuffle up their order. For example, consider the set of numbers . A permutation or shuffled order of these numbers could be

. To get a permutation there is a series of steps that you can go through to go from

to

. Permutation groups study these steps. You can check that you can combine (binary operation) these shuffling steps, you can do nothing (the identity operation), you can undo each of them (inverse element), and you can check that they are indeed associative by rigorously defining the shuffling as a (bijective) function on the set

to

. These make the permutation group a group. We denote the set of all permutations of the set

by

.

Note permutation groups are not, in general, commutative. This means that preforming shuffle A and then B is not the same as preforming B and then A. The order matters in general.

Matrixes

Our last example is a set of square matrixes with the operation of matrix multiplication. For those who recall, a square matrix has a multiplicative inverse if and only if its determinant is non-zero. So, we have the group.

.

There are too many groups!

We’re interested in different groups, but we’re also very lazy and don’t want to have to do more work than we need to (a trend in mathematics). We don’t want to have to classify all possible groups, that’s ridiculous! For instance, consider the subgroup of the additive group of complex numbers where the real and imaginary parts are equal,

.

*Please check that is a group.

Once you start to work with you’ll might notice something. Consider the elements

and

. When we add them, we get

We are writing a lot of extraneous stuff that we don’t have to. Namely, all the imaginary parts of the complex numbers. Since the real and imaginary parts of all are the equal, we don’t really have to keep track of them both right? So who not just consider the sum

and then remember that we need to tack on a

to the

? Indeed, we can do this! But, by doing this simplification we are essentially working with the additive group of real numbers

and not with

, at least until the last step.

In some sense, and

are the same group. They both convey the same information.

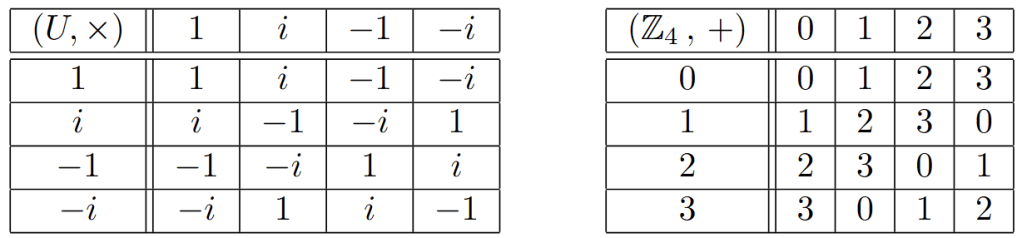

Consider the multiplicative group where

(you should check that this is indeed a group) and the additive group

. Let’s write out a multiplication table for

and an addition table for

.

Take a look at the two of them. Do you notice anything? No? Take another look, once I tell you cannot unsee it!

Ok, consider what would happen to teh group if you swapped multiplication with addition modulo 4 and then swapped

?

Take a moment to look at the tables to see what would happen.

Answer: The two tables would be identical! So, in some sense is the same group as

. Their tables carry the same information as each other. We’d like to formalize the notion, “the groups are the same”. This is where isomorphisms come into play.

What features do we want to capture when we say that two groups are really the same group? Well, if we are saying that is the same as

then the set

and the set

better have the same number of elements when they are finite sets, and when they are both infinite sets we want to make sure that they are the same size infinity. This is done by making sure that we have a one-to-one correspondence between

and

. Or, that we have a bijection

.

What else?

We said that was the same as

since their tables matched one another. Well, they match once we made the appropriate substitutions. Since we want a bijection between the two groups, if we force the bijection to have the property

then we’d capture this. For example, let be defined by,

First, note that is a bijection. Now note that we also have

As well as,

and

and this works for every pair of elements in , as you can check. This leads us to the definition of a group isomorphism.

Group Isomorphisms Formally

Definition (Group Isomorphisms): Let and

be two groups. We call a function

a group isomorphism if,

is a bijection and

for all

.

When this happens, we say that and

are isomorphic to one another and we write:

or

when the operations is understood.

*We will call property 2. the isomorphism property.

Using the groups and

we’d now be able to say

. Recall we also claimed that

and

are the same. Now we can sound more mathematically savvy and say that

and

are isomorphic. But, to say this we must prove it by finding an isomorphism! Can you guess what it might be? What about,

where

.

Let’s prove is a bijection first. Recall, that we must show that

is a bijection we must show that

is both injective and surjective.3

Injective: Let . Then, by definition

and this implies

.

Surjective: Let . Then letting

we have

.

Now, we must show that has the isomorphism property. Consider

. Then,

.

Therefore, is an isomorphism and hence

.

Some Properties of Isomorphisms

Let’s go through some properties that isomorphisms enjoy!

Isomorphisms map identities to identities!

Lemma 1: Let be an isomorphism between the two groups

and

. Denote the identity in

by

and the identity in

by

. Then,

.

Proof: Let is an isomorphism between

and

. Denote the identity in

by

and the identity in

by

. We know that

which implies,

where we used the isomorphism property. Therefore,

which upon multiplying by we get (using associativity),

which gives,

.

Concluding the proof.

Isomorphisms map inverses to inverses!

Lemma 2: Let be an isomorphism between

and

. Let

, then

.

Proof: Let be an isomorphism between

and

and let

. Then

.

Where we used the isomorphism property and Lemma 1. Now we solve for

.

And after you parse that mess, we conclude,

.

How to tell when groups are not isomorphic

We know how to prove that two groups are isomorphic to one another, but how would you be able to tell when two groups are not isomorphic to one another? Unfortunately, (or fortunately if you like a challenge!), there is no one method to determine when two groups are not isomorphic, however, there are a few tips that I can give.

- Clearly if one of the two groups has more elements then there cannot be a bijection between the two group’s sets.

- If one group is cyclic and the other is not then the groups cannot be considered “the same”. (Note you can try to prove: if

is cyclic with generator

and

, then

is cyclic with generator

. Where we are assuming that

an isomorphism between the two groups.)

- You can check the elements in one group’s order and compare them to the order of the second group’s elements. For example, if there is an element

that has order 2 and every element in

has order larger than 2, other than the identity, then the groups aren’t isomorphic.

- In general, the idea is to find properties that one of the groups has that the other doesn’t have.

Cayley’s Theorem

When you learn group theory you might be caught off guard by all the different groups that you can form. There are so many different systems that can be analyzed by groups theory. Such a permutations, the real numbers, modular arithmetic, matrices, functions, regular polygon symmetries, etc. Even with all these possibilities, there is an underlying structure that they all share. That it, they’re all groups! And from this, we can prove something that all groups share with one another. It’s deep, quite unexpected, and we will end on this theorem.

Theorem (Cayley’s Theorem): Every group is isomorphic to a group of permutations.

What?!?! How strange is this? Every group is isomorphic to a group of permutations. Yup, ,

,

,

,

,

,

, and more are all isomorphic to groups of permutations. So, if you have not gone back to read Permutation Groups… I think it’s time! And if you don’t want to read my article, check out Art of Problem Solving: Permutations and or Art of Problem Solving: Symmetric Group.

How might we prove Cayley’s Theorem? We want to show that some arbitrary group is isomorphic to a group of permutations. We have nothing to permute except the elements of

. So, maybe we should focus on permuting the elements of

itself.

Let’s try this out.

Recall is a permutation of

if and only if

is a bijection from

. Let’s try to find some bijections

. One of the simplest bijections that you might guess is given by left multiplication by some fixed element

. I.e.

.

We will, in a moment, prove that is a bijection from

to

. I challenge you to prove it first!

However, we’re not done with the proof just yet. We must then show that is isomorphic to a group of permutations. The permutations in question will be the set

that we just found as we run through all of the

. To finish the proof, we must find an isomorphism between to

and the group of

s Ok, let’s do this!

Proof: Let be a group. Fix

and define the function

by

We claim that is a permutation of

. In order to show this, we must show that

is injective and surjective.

Injective: Let which implies

. Multiplying on the left by

gives,

or better yet,

.

Surjective: Let and consider

. Applying

to

gives

.

We conclude that is indeed a permutation. Furthermore,

is a permutation for any

. This motivates a shift in attention to the set of permutations,

Which we must show along with function composition is indeed a group. I’ll leave this part to you, as hint the identity in

is

where

is the identity in

and

.

We claim . To show this we need an isomorphism between the two groups. My first guess would be

. And luckily enough it works! Let’s prove it.

Injective: Let . Thus, for any

we have

and hence which implies

.

Surjective: Let . Then,

maps to the desired permutation

.

Isomorphism property: Let . Then,

And,

.

Since are all functions we can apply them to some

. Doing tis we deduce,

concluding our proof!

Closing Remarks

Isomorphisms are fundamental to all of mathematics. We covered group isomorphisms, there are ring isomorphisms, representation isomorphisms, vector space isomorphisms, etc. All of them are similar to one another, in the sense that they are making rigorous the idea of two things being equivalent to one another. The word equivalent is bolded for a reason. It’s because of this surprise last theorem:

Theorem: Isomorphisms form an equivalence relation between groups of the same order.

Proof: To prove isomorphisms form an equivalence relation we must prove three things: (1) reflexivity , (2) symmetry if

then

, (3) transitivity

and

then

.

(1) I leave you to show that the identity map defined by

for all

.

(2) Suppose , then there is an isomorphism

. Since

is a bijection there is an inverse function

which is also a bijection. We just need to show that

has the isomorphism property.

Where we used that is a bijection so that any

is equal to

for some

, as well as the fact that

has the isomorphism property.

(3) Let and

. Then there are isomorphisms

and

. We claim that

is our desired isomorphism. First, recall that the composition fo two bijections is still a bijection (see if you can prove this if you haven’t heard this before). To see that

has the isomorphism property we need some notation. Let our groups be denoted

. For any

we have,

as desired.

If we wanted to classify all possible groups, we have reduced our work load since we could now classify all groups up to isomorphism. This is a huge deal because it’s a lot less work, and a lot more fun! For example, there are only two different groups, up to isomorphism, with order 4,

Were the group is the set

along with addition defined by

.

You can tell that are not isomorphic because

is cyclic and

is not.

But how amazing is this fact, any group with four elements must be either isomorphic to or

! I challenge you to prove this, and as a hint, consider the multiplications table you can have for a group with four elements. Leave your proofs/ questions in the comments!

As always, thank you and have some fun!

Footnotes:

- Two numbers

and

are `congruent’ to one another modulo

(the modular arithmetic version of being equal) if

and

have the same remainder when we divide

by

and

by

. Or, more precisely

. Where we read

as

is congruent to

modulo

. For example, let

. Then we’d say that

since either

. Or because

and

. ↩︎

- This is too deep and interesting to convey in a foot note! So, check out either Newbie at Number Theory: (Part 3) ax+by=1 and or Newbie at Number Theory (Part 5): Modular Arithmetic if you are still interested. ↩︎

- Let the function

be a map between the sets

and

Recall that injective is the fancy math word for one-to-one. Simply put, every element in the range has a unique element in the domain that maps to it. Or, ifthen

. And surjective means that every element in the codomain gets mapped to it. Or, for all

there is some

such that

Lastly, when a function is both injective and surjective, it’s called bijective. So another way of saying thatis a permutation is to say that

is a bijection from some set

to itself. ↩︎

Leave a comment