MythBusters Motivation

I was recently rewatching one of my favorite shows called, MythBusters. Specifically, The Wheel of Mythfortune season 9, episode 21 in which they test the Monty Hall Paradox. The Monty Hall paradox is confusing upon first (and sometimes tenth) glance, but it isn’t a paradox, and no math website/YouTube channel/blog/probability textbook would be complete without a discussion of Monty Hall probabilities!

For those who haven’t seen the episode and who haven’t heard of the Monty Hall Problem I’ve linked the MythBusters episode at the end of this article. But here is the problem for those who don’t want to watch the episode yet:

You are on a game show where you are given three closed doors labeled 1, 2, and 3. Behind one of those doors is a grand prize and behind the other two is nothing. The host asks you to choose a door. After you make your choice, the host will open an empty door that you didn’t choose. Finally, the host then gives you the choice of swapping your chosen door for the only other door left. The question is: do you want to switch doors?

Let’s illustrate with an example.

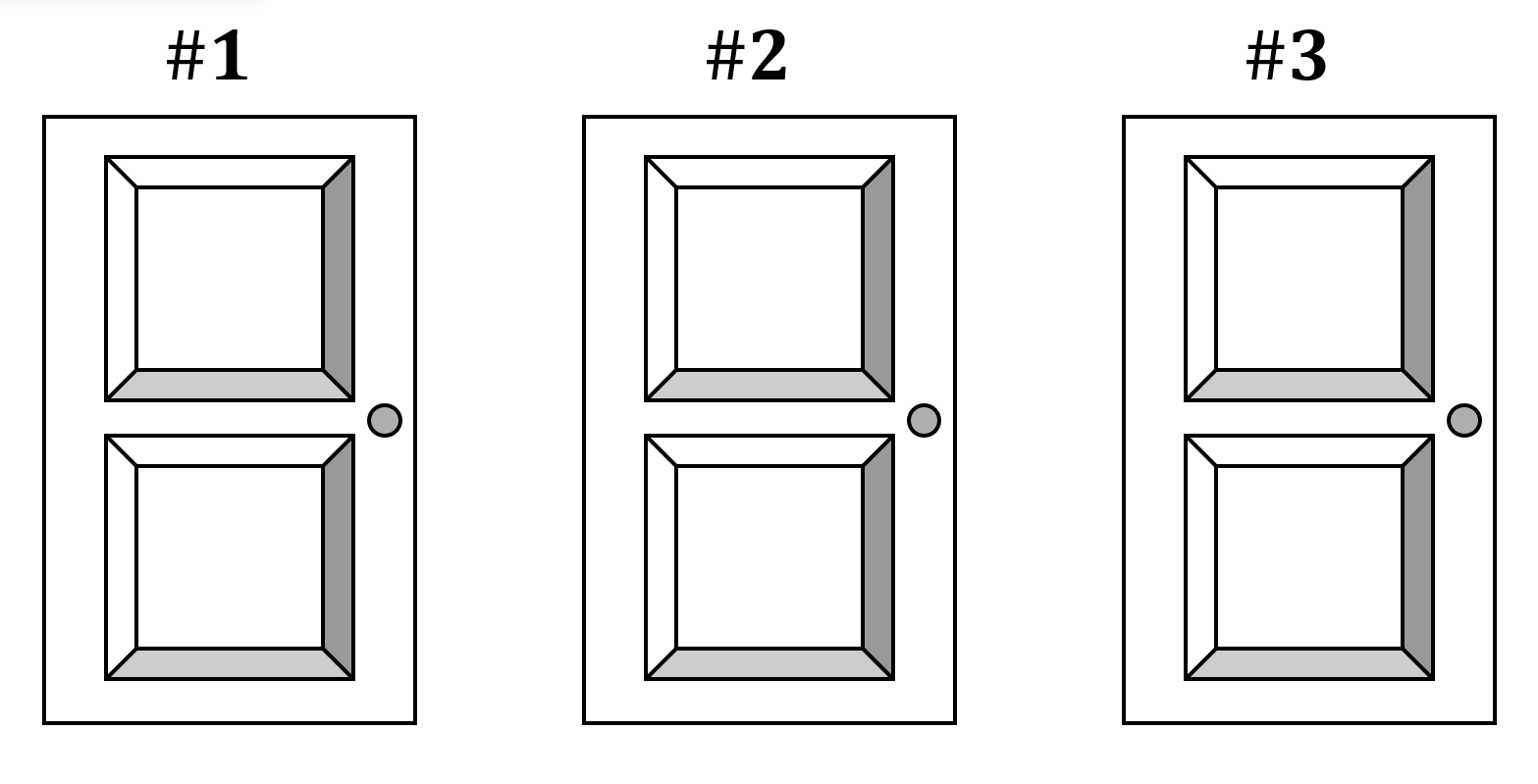

Host: Please pick one of the doors #1, #2, #3.

Us: We choose door #2.

Host: Please open door #1 to show there is nothing behind it.

Host: Would you like to keep your first choice of door #2 or switch to door #3?

Take a moment to think this through. What’s the best possible strategy you can employ to win the prize?

Hedging Our Bets

Conventional wisdom (and the myth) goes like this, “Since we are down to a 50/50 choice between door #2 and door #3, it doesn’t matter, therefore I will keep door #2.”

The MythBusters then tested two claims made in that statement:

- It doesn’t matter if you switch doors.

- Most people won’t switch their door.

We will focus, in a moment, on the first more mathy claim. But, let me mention that according to the data that the MythBusters gathered, most, if not all, people will stay with their original door because switching your choice amounts to nothing because of the first claim.

It’s NOT 50/50

In regard to the first claim, if you want to maximize your chances of winning, sticking with your original choice is not the best thing to do. It is much better to switch to door #3 than to keep door #2. It’s not very easy to see why, and this is where the paradox comes in.

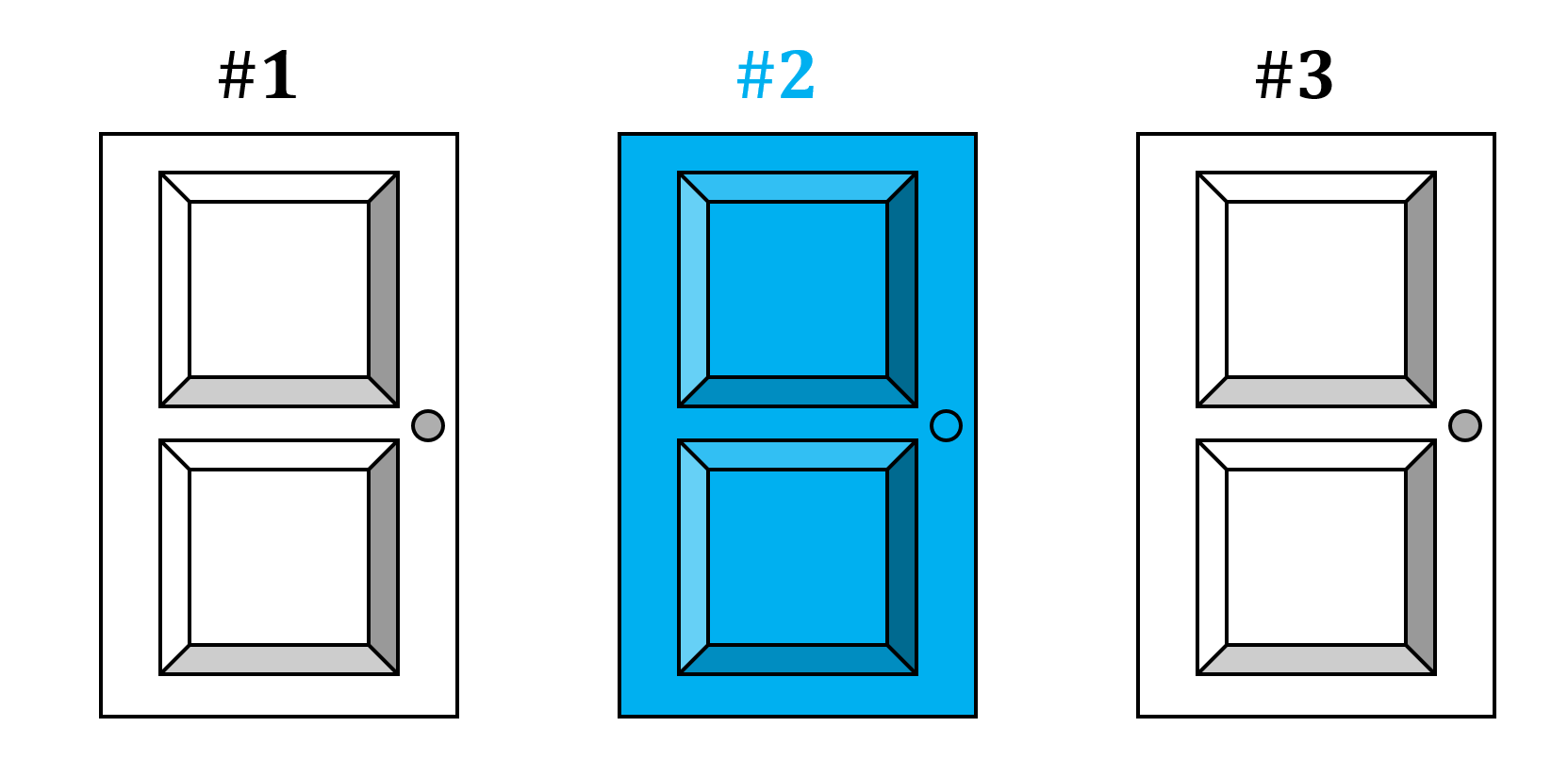

Consider what is happening. We choose door #2 knowing that the host will then reveal that the prize isn’t behind door #1 or #3. In our example, it’s not behind #1. So, what happens to our probabilities as this process transpires.

Beginning: Each door has a 1/3 probablility of hiding the prize.

After We Choose: There is a 1/3 probability that we are right and a 2/3 probability that we are wrong, i.e. there is 2/3 probability that the prize is behind door #1 or door #3.

After The Host Reveals an Empty Door: Nothing changes regarding what we just said, there is still a 1/3 probability that we are right and a 2/3 probability that we are wrong. However, we now know that if we are wrong, then the prize isn’t behind door #1. Since there is a 2/3 probability, we are wrong, there is a 2/3 probability that the prize is behind door #3.

Conclusion: The probability that the prize is behind door #2 is 1/3 and the probability that the prize is behind door #3 is 2/3. Thus, it’s better to switch.

How amazing is that! By switching we double our chances of winning! Isn’t math(s) great!

The Unpredictable Host

Let’s look at a slight variation on this classic problem! How would our strategy change, if at all, if the host did not know where the prize was? In this situation the host is told to simply open a random door that you didn’t choose.

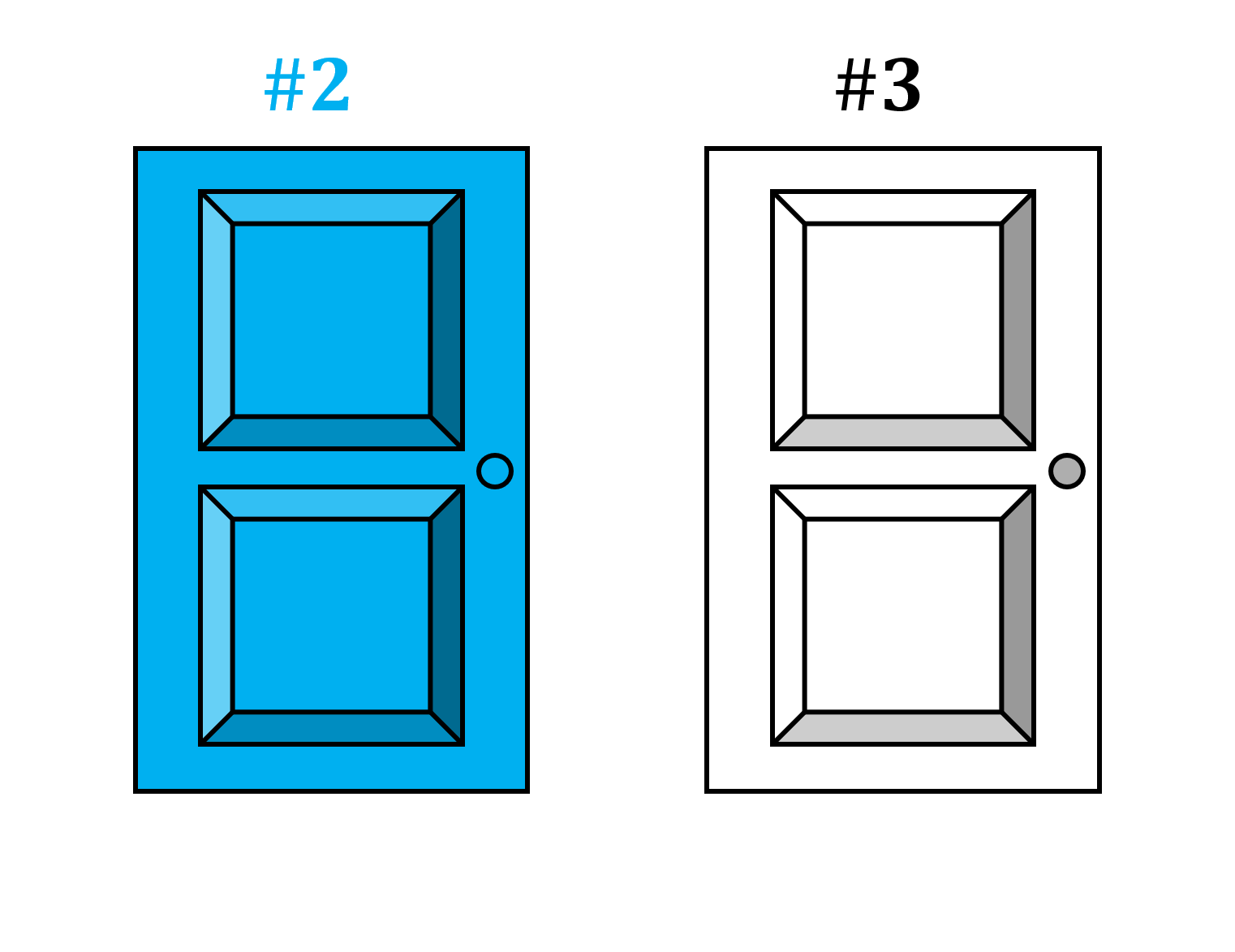

Now we have the situation where you choose door #2 and the host randomly opens door #1 to reveal nothing (note in this situation the host could have opened the door with the prize but didn’t). Should you switch?

Well, let’s see!

We want to determine the probability that you guessed correctly given that the host opened an empty door. Remember, the host doesn’t know where the prize is, so the host could have opened the door with the prize but in this situation didn’t.

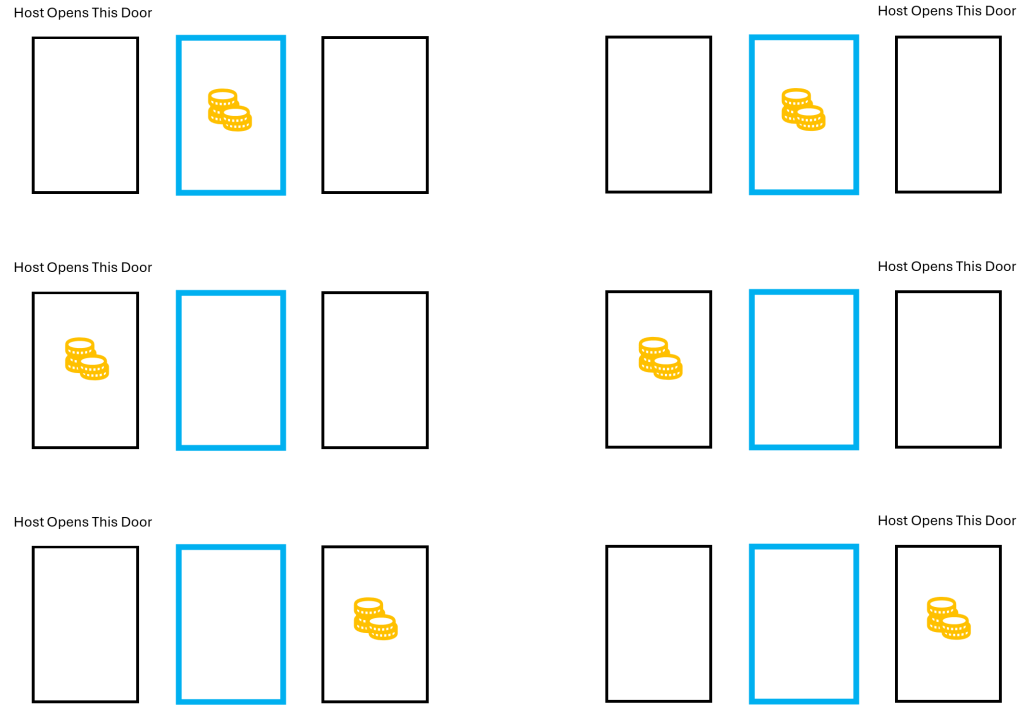

What are the possible outcomes for this game? Let’s list out what can happen using our choice of door #2.

Notice that we have, at first, six possible outcomes. However, since we are working under the assumption that the door the host opened was empty, we can widdle down these six to just four of these outcomes.

Within these four outcomes we are only correct in two of them.

Conclusion: In this case there is a 1/2 probability that we are correct. Therefore, this situation that you might have guessed it was.

How strange is it that our best strategy depends on what the host knows! If the host is clueless to where the prize is, in some sense so are we. If the host knows where the prize is then we have a better chance of finding the prize. How awesomely counterintuitive!

Closing Remarks

The Monty Hall Paradox/Problem is perhaps the most famous math problem that highlights how unintuitive probability can be, and how we can be led astray if we aren’t careful. In my opinion, this is why this problem is so famous and why so many math(s) related blogs or YouTube channels have some content discussing it.

If there is one thing to take away from this article, besides how great math(s) is, it’s how easy it is to be misled by faulty (but believable) logic when we aren’t careful or trained. If you hadn’t heard of the Monty Hall problem before, or read this article, I bet you would have been content thinking that the original problem was indeed a 50/50 situation not the 1/3 to 2/3 situation that it really was.

It makes me think of all the situations in my life where I’ve fooled myself. I think Richard Feynman put it best, and we will end with a quote by the great thinker,

“The first principle is that you must not fool yourself—and you are the easiest person to fool.” — Richard Feynman

Some Fun Videos

Numberphile playlist on the Monty Hall Problem here.

Leave a comment