For the first Pi day after having started akickinthediscovery.com I figured that we should do something special! We’re going to show that the sum of the reciprocals of the squares equals… a surprise alla Euler:

*******Tangent: We call numbers like

There is a wonderful history to this problem (the sum of the reciprocals of the squares) and I can in no way describe it better than the math historians out there, so I defer the history to the historians! But, just in case you don’t want to leave this page, long story short no one could solve this problem for a long time. Everyone wanted to know what this sum converged to (the limit version of equaling), but no one, not even the greats like Newton and Leibniz could do it. Not until Euler at only 28 years old, who was unknown at the time, came along and showed the sum of the reciprocals of the squares equals an utterly surprising value. He ended up proving this in a few ways, however, I’d like to prove it in my favorite of his methods. I’d like to give much thanks to William Dunham and Stony Brook University for teaching me this proof!

Theorem: (Euler) The sum of the reciprocals of the squares equals a surprise:

****Note: Euler did not have rigorous analysis so some of these steps would need more through justification than he gave, and therefore what I give.****

Here’s some music to listen to while you read this wonderful proof!

Proof: To begin we will write the sine function as an infinite product. How might we go about this? Well, we know that the zeros of sine are any of the integer multiples of

*Where we used the fact that

Where we choose

Moral, we have the following infinite product for sine

Now let’s’ make our first, of many, substitution

Since we are working with a product, yuck, we take some natural logs of both sides to get a sum,

The problem is that we now have a bunch of logs that make things more difficult. To get rid of this we take the derivative with respect to

With a little rearranging,

Now Euler tells us to make another (and more complex haha math pun) substitution:

*Cue the thought: Where on Earth is Euler going with this argument?*

With this substitution we get:

Now we use Euler’s identity:

Which we promptly use to simplify the left hand side

Now is where this gets messy! We will use what we just found and combine it with

But let’s not lose track of the infinite sum we have this equal to:

and recall that the whole goal of this was to find the sum of the reciprocals of the square nummm…berrr…sss wait just a moment!!! Take a look at the right-hand side of the above equation, if we let

Aweeeeee we’re so close! But can we do anything with

L’Hôpital’s rule (applied to our situation):We ended up with

So we just need to differentiate the numerator and denominator of

We’re finally done, let’s plug in

Oh not again! I thought we were done… I guess we will use L’Hôpital’s rule a second time… hmmm… I don’t like this, it reminds me of calculus homework (this proof was actually in Euler’s Calculus textbook)! But we carry on

We’re finally done (Déjà vu), let’s plug in

You’ve got to be kidding me! No way we need to use L’Hôpital’s rule a third time, who would come up with this?????

Deeeeeeeep breathssssss….

Let’s give it one more go:

This seems promising, we can’t get zero in the numerator! Let’s plug in

WOW how amazing is this??????? It’s incredible! Our final result is,

Who would have thought that summing square numbers would result in something with the circle constant

Closing Remarks about Pi

Did you know it was Euler who standardized the use of the Greek letter

“Why is

Great questions! Of course, I don’t have the answers, but I would say that

discovered by the great mathematician Srinivasa Ramanujan. And more and more! This is why it’s the spokes constant of math and why I think that it deserves a day of celebration.

Let me know in the comments your favorite places where

For those who want even MORE pi, here are some of my favorite videos dedicated to pi in no particular order:

FUN

*Sorry I couldn’t get the

- Why is pi here? And why is it squared? A geometric answer to the Basel problem-3Blue1Brown

- Euler’s Pi Prime Product and Riemann’s Zeta Function-Mathologer

- Tau vs Pi Smackdown – Numberphile

- Euler’s infinite pi formula generator-Mathologer

- Strings and Loops within Pi – Numberphile

- Pi hiding in prime regularities-3Blue1Brown

- Calculating Pi with Real Pies – Numberphile

- Can we calculate 100 digits of π by hand? The William Shanks method. – Stand-Up Maths

- How Pi was nearly changed to 3.2 – Numberphile

- Euler’s real identity NOT e to the i pi = -1 -Mathologer

- e to the pi i for dummies -Mathologer

- The most unexpected answer to a counting puzzle-3Blue1Brown

- New Recipe for Pi – Numberphile

- The biggest hand calculation in a century! [Pi Day 2024]- Stand-Up Maths

- Calculating π with Avogadro’s Number- Stand-Up Maths

- Using an Out-of-Control Car to Calculate π. – Stand-Up Maths

- Why π^π^π^π could be an integer (for all we know!). – Stand-Up Maths

- How pi was almost 6.283185…-3Blue1Brown

- Why π is in the normal distribution (beyond integral tricks)-3Blue1Brown

- There’s more to those colliding blocks that compute pi-3Blue1Brown

- The Wallis product for pi, proved geometrically-3Blue1Brown

- We calculated pi with colliding blocks-Stand-Up Maths

- Save Your Calculus Grade-Mathologer

- Pi is IRRATIONAL: simplest proof on toughest test -Mathologer

Footnote:

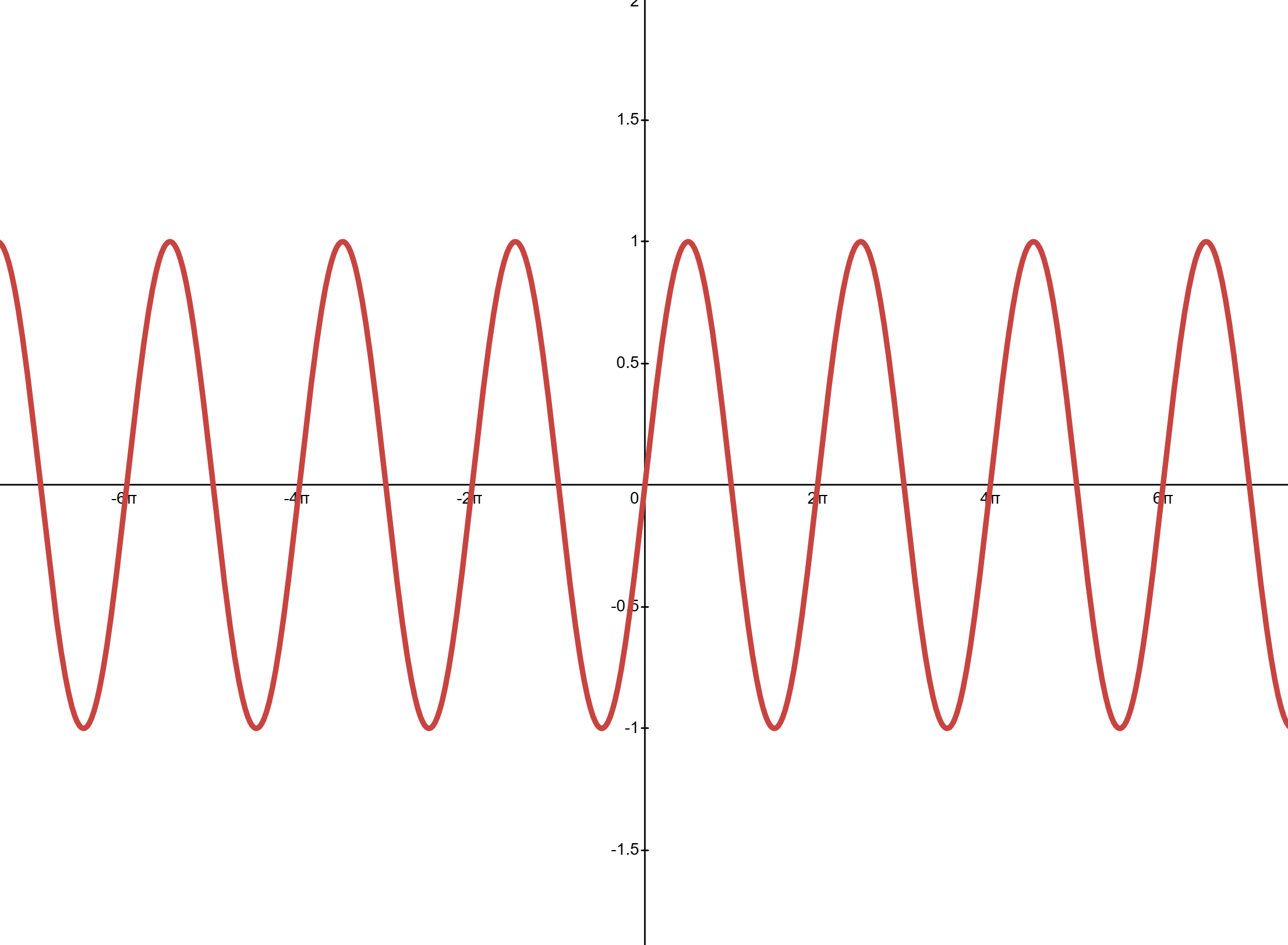

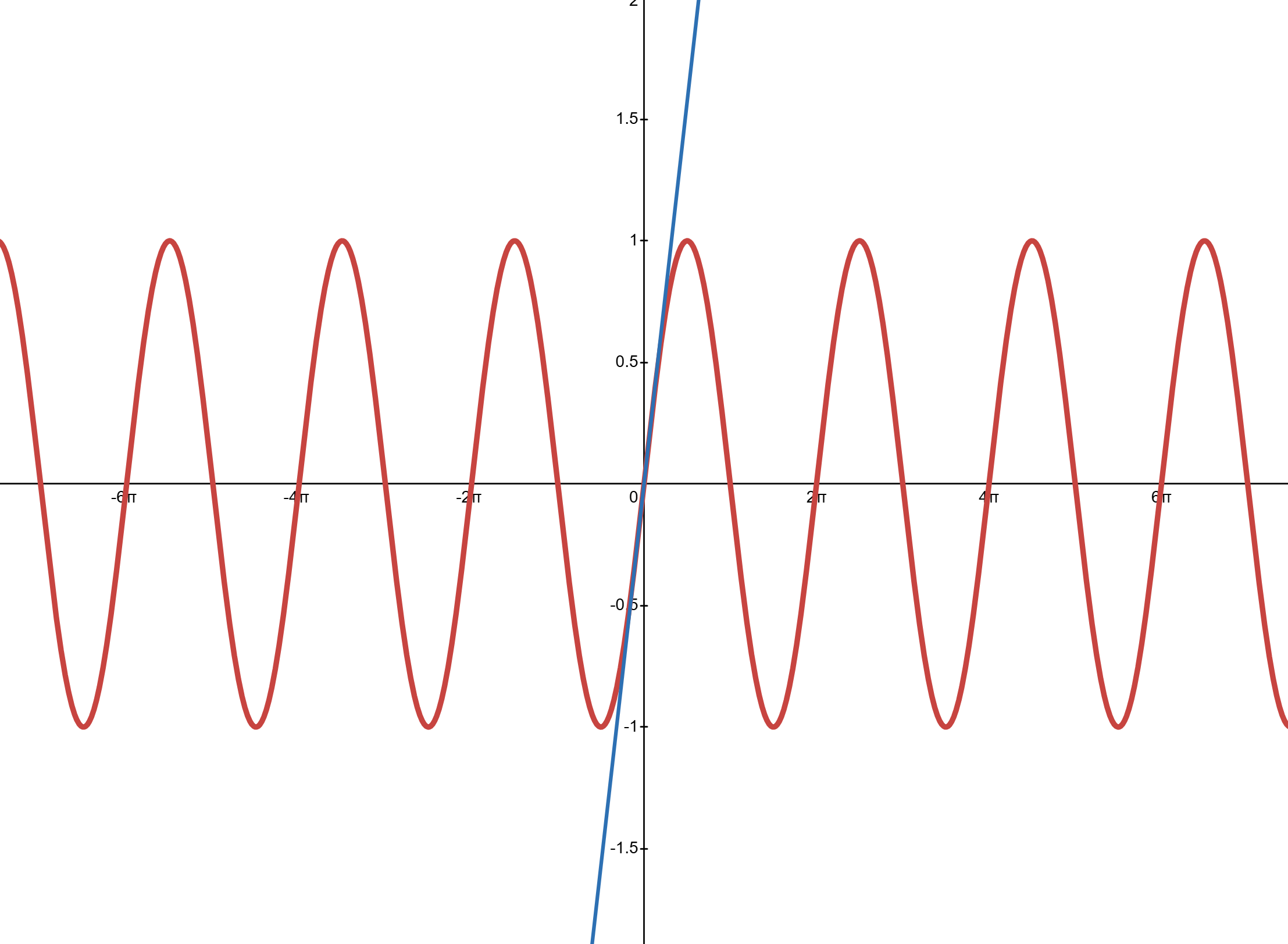

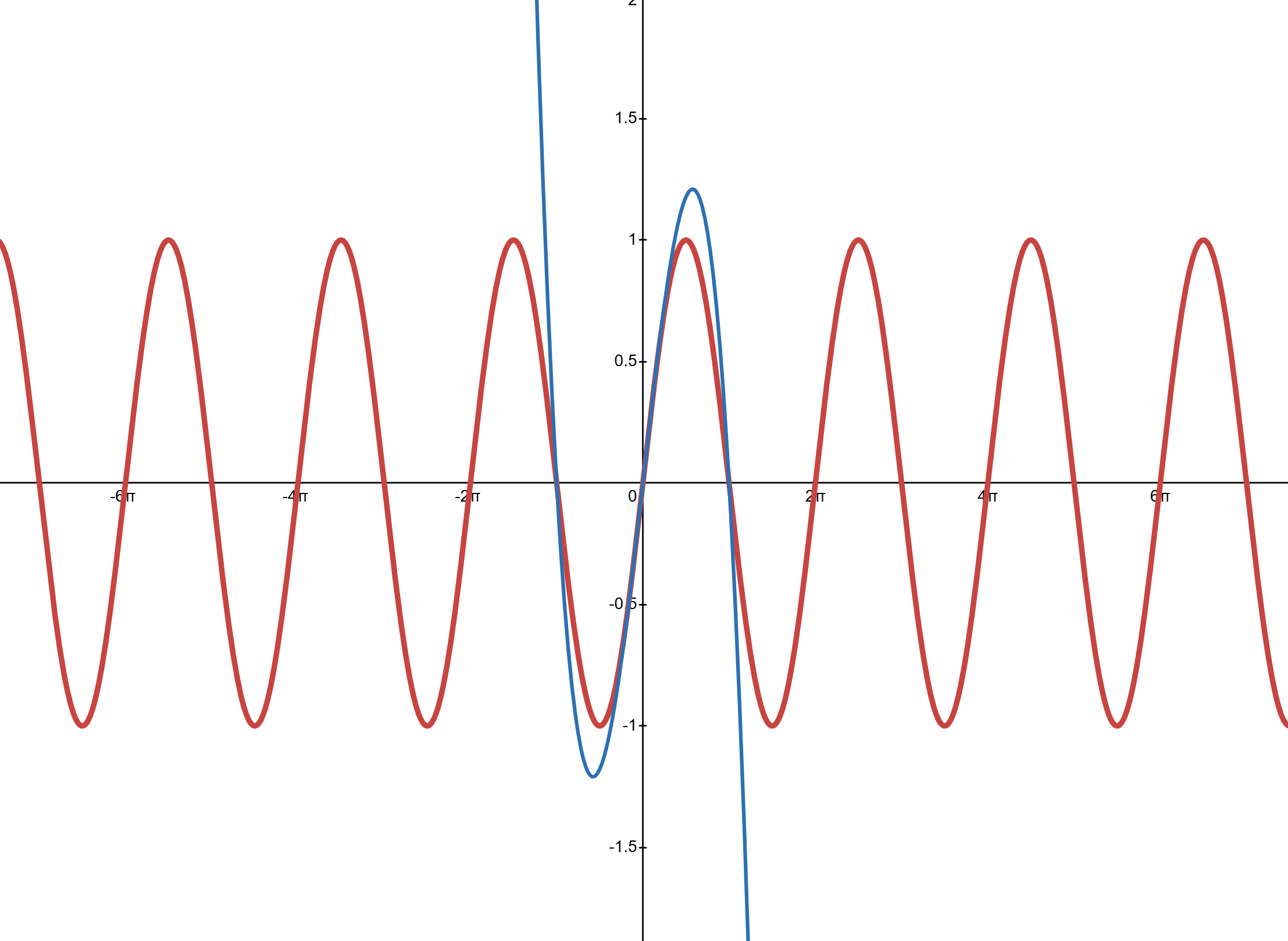

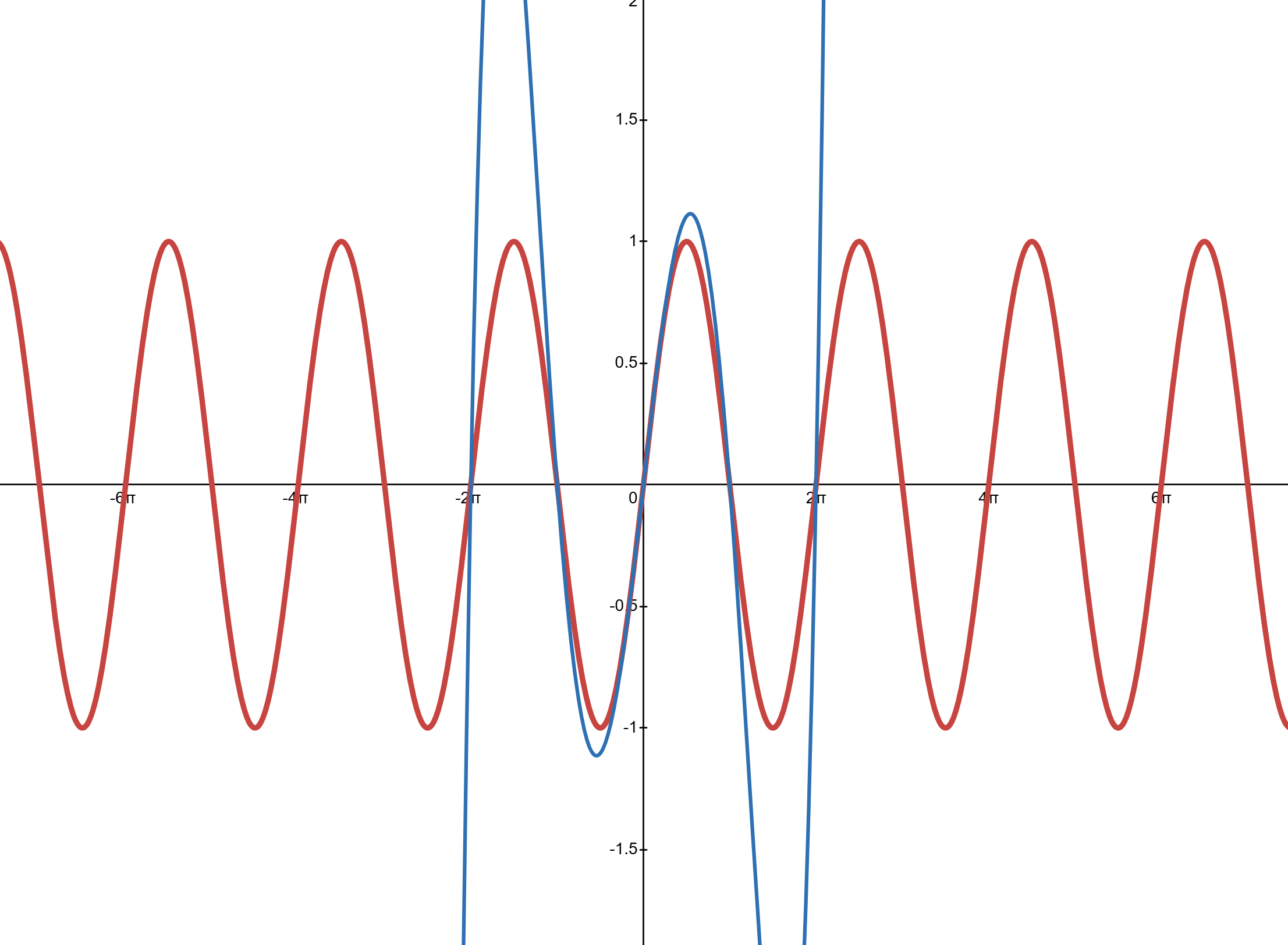

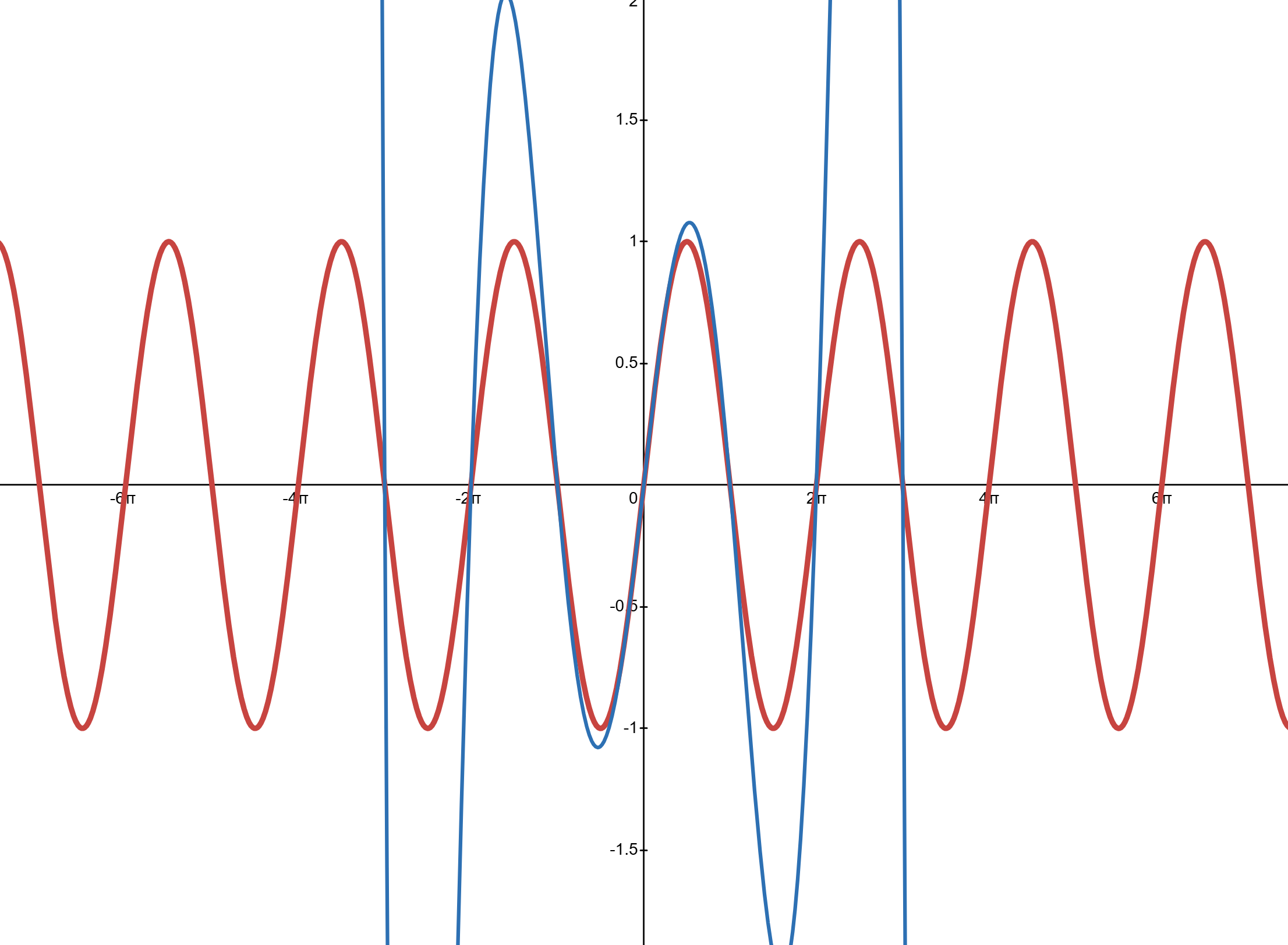

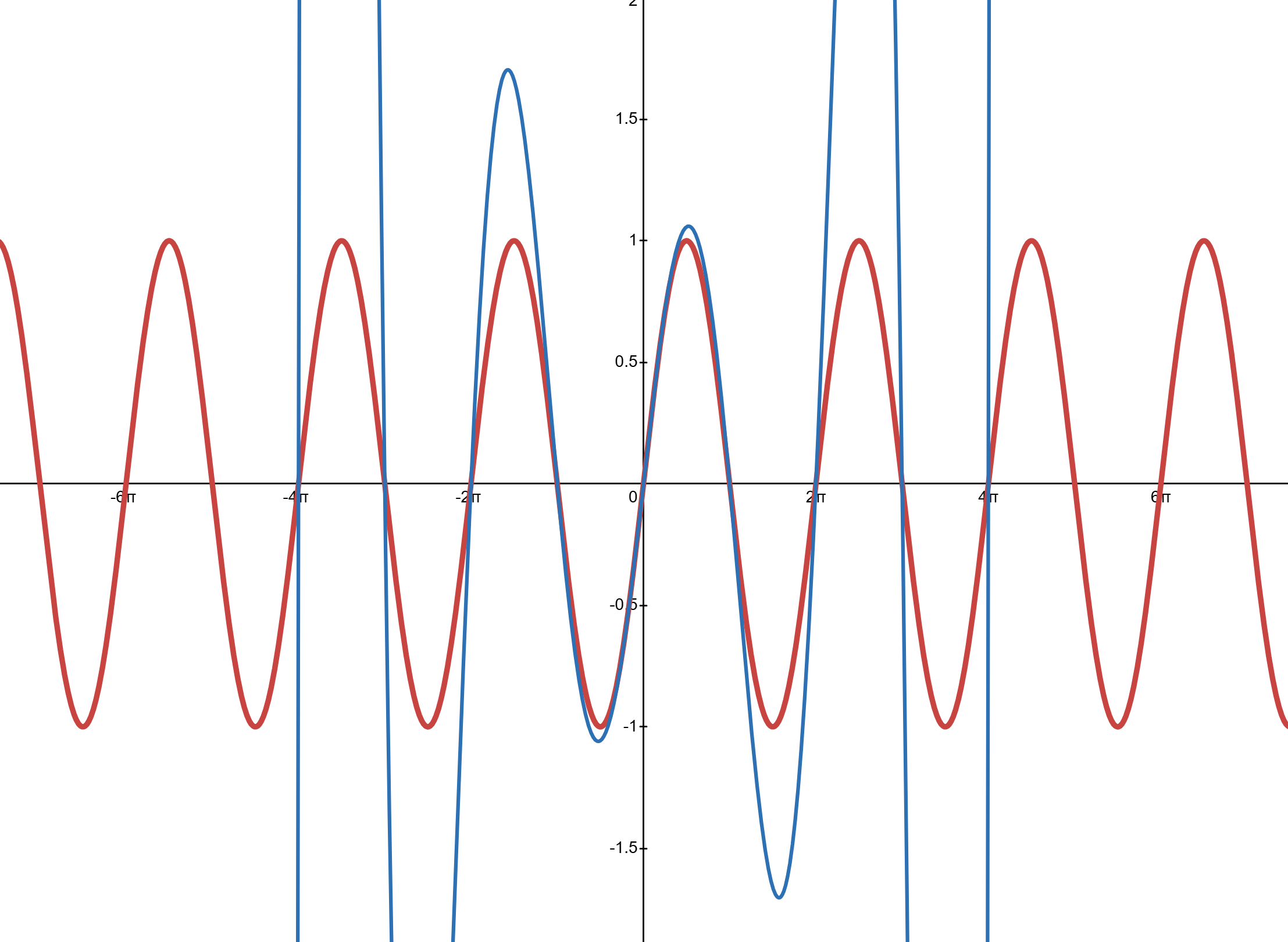

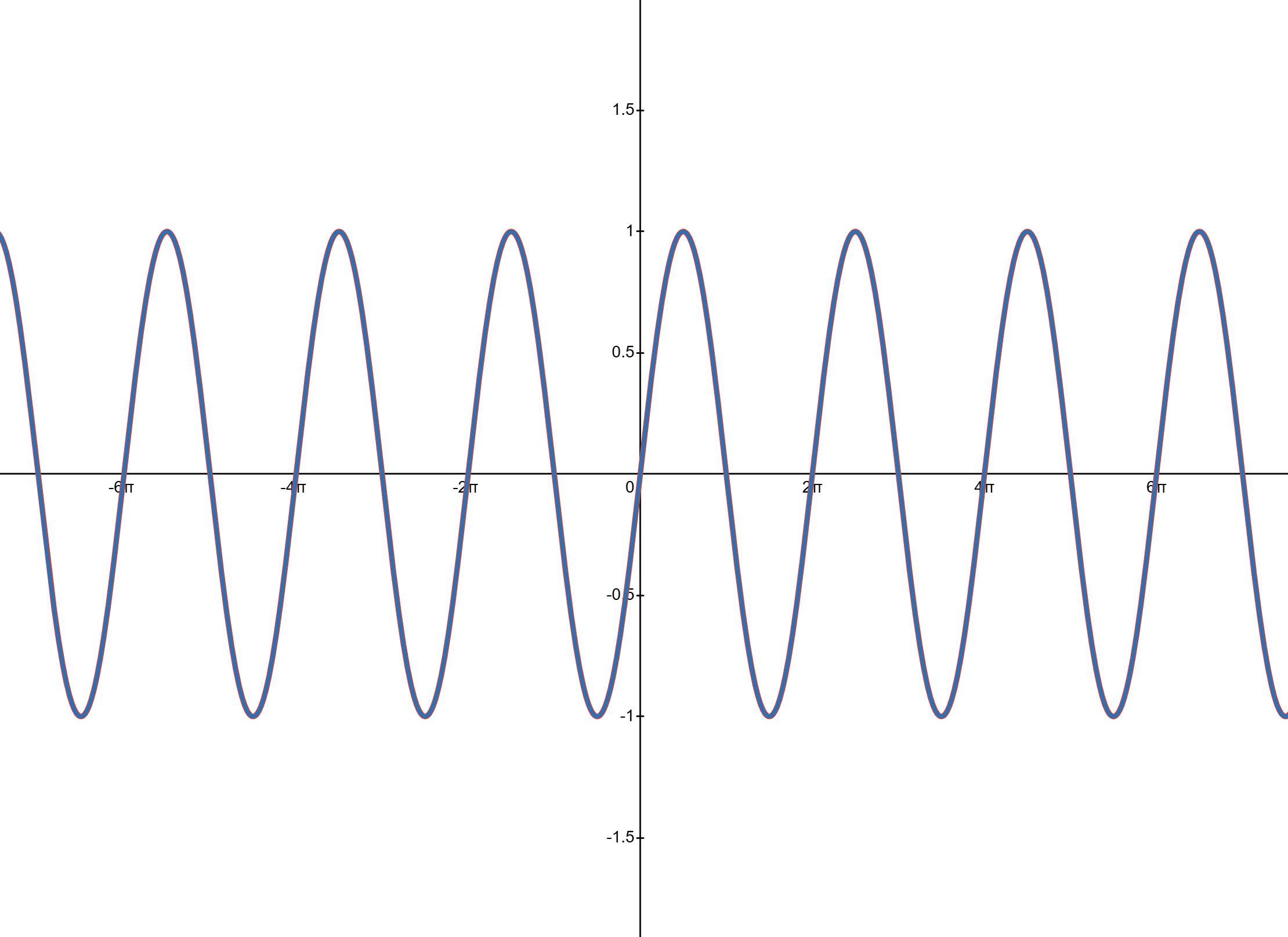

- Below is a series of graphs, the red is always

Slide 2: Blue line is:

Slide3: Blue line is:

Slide 4: Blue line is:

Slide 5: Blue line is:

Slide 6: Blue line is:

Slide 7: Blue line is:

Slide 8: Blue line is:

and then all the way up to 1,000,000.

Slide 9: Blue line is:

Leave a comment