Thomae’s Function aka The Stars over Babylon aka The Popcorn Function

* Note it’s assumed the reader has heard of limits for both sequences and functions, the connection between limits for sequences and functions (Called Heine’s Continuity Criterion), and continuity for functions. I haven’t decided whether or not there will be a blog post about any of these topics. But it you want that, please comment so and I will be more likely to do so! *

Ok, so you’re familiar with continuity somehow! If you have only taken calculus or physics, then you probably have a very intuition-based knowledge of continuity, rather than one based on the definition of continuity. However, just as in science, sometimes an intuition only approach in math can lead you astray! A great example of this is when looking at the continuity of Thomae’s function (aka the popcorn function or The Stars over Babylon). Before we get to this awesome function, let us ask some questions about functions and what types of continuity they can have to warm up a little.

(Everything is in the context of functions of real numbers)

- Can you have a function continuous everywhere?

- Is there a function that is discontinuous at one point?

- Is there a function that is discontinuous at two points?

- Is there a function that is discontinuous at countably infinitely many points?

- Can you have a function continuous nowhere?

- Can you have a function continuous at infinitely many points and discontinuous at infinitely many points? (countably or uncountably)

- Oooo… can you have a function continuous at irrational numbers and discontinuous at all rational numbers?

I’m guessing that your calculus intuition might have helped with the first few questions, and then less so towards the end.

Let’s run through some of these questions really quick. We won’t prove our answers here; however, the same logic we will use for Thomae’s function will apply to the more complex questions above.

Can you have a function continuous everywhere? Yes, like f(x) = x.

Is there a function that is discontinuous at one point? Yes, for example, the sign-function. Which is defined to be equal to +1 for positive numbers, -1 for negative numbers, and 0 for x=0.

Is there a function that is discontinuous at two points? Yes, for example, the rectangular-function. The key idea is similar to the sign-function.

Is there a function that is discontinuous at countably infinitely many points? Take your guess! If you think so, try to think of an example and put in the comments. If you don’t think so prove why you cannot have one!

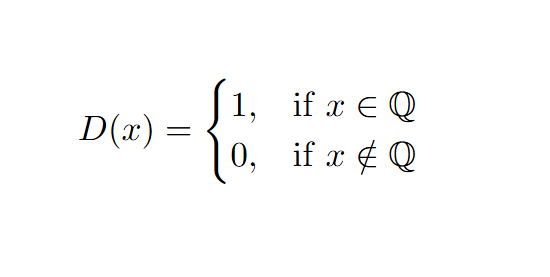

Can you have a function continuous nowhere? This one is where I think calculus intuition starts to fail us. The answer is surprisingly yes! An example is called Dirichlet’s function. It’s a very weird function and is defined as follows,

It’s not a function that lends itself to being graphed and we won’t show why this function is continuous nowhere; however, you may be able to do this yourself after reading about Thomae’s function!

Oooooo… can you have a function continuous at irrational numbers and discontinuous at all rational numbers? We skipped one question, since the answer to this question is YES! So, the former question has an answer of YES when you want uncountably many continuous points and countably many discontinuous!

Wait! What? You can have a function that is continuous at all the irrational numbers and discontinuous at all the rational numbers? This is where you think: How’s that possible? Prove it! And we shall. With Thomae’s function!

Thomae’s function is continuous at all irrational numbers and discontinuous at all rational numbers. Let’s show why!

Finally, Thomae’s Function

The Definition:

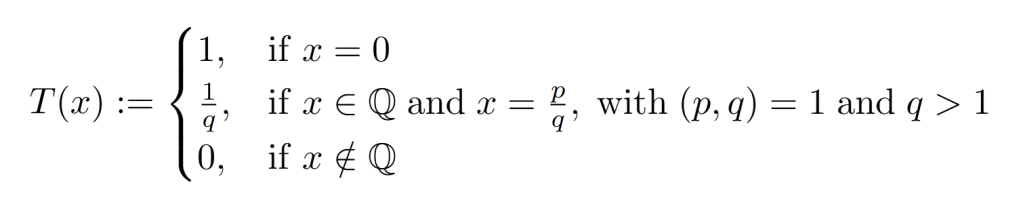

We define Thomae’s function to be the following:

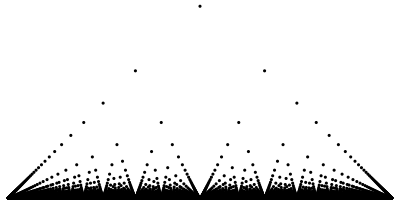

Very strange indeed. Here’s a great visualization of T before we study it.

By Smithers888 – Own work, Public Domain, https://commons.wikimedia.org/w/index.php?curid=4957683

Sketch:

We’ll soon see it’s not too bad to see that T is discontinuous at all

Let

The key idea is the following: We want to get within one-tenth of

Consider the set of all rational numbers

Some elements in

Note that

If we want some rational number to get closer to

does what we want it to do. Indeed, since for all

Thus,

To recap, we showed for

Proof:

We aim to show that

(Step i) Showing that

Let

(Step ii) Showing that

Remember we’re doing it by definition of continuity.

Let

We claim letting,

works! The reason is similar to what we remarked earlier. Also, note that $\delta>0$ since no rational number can equal

Observe, for all

Concluding the proof!

Closing Remarks

How awesome is Thomae’s function. Answer: It’s pretty darn cool! I hope I made this more palatable for those who are taking Real Analysis or who have taken the class. I admit this is an advanced blog post; however, I hope that it was interesting!

Any who, you’re probably either sweating from exhaustion for making it to the end (thank you by the way). Or you’re sweating from excitement. In which case you should try to show that Dirichlet’s function is continuous nowhere. If you want a hint read the next line. If not, go have fun!

Oh, one last thing. You can tweak the argument to show that

Hint…

Try to come up with a justification why you can make two sequences

Leave a comment