Have you ever found it interesting that one of the first things we learn in school (and sometimes even before we start school) is how to count, and yet there are many interesting and challenging problems/concepts that can come from simply counting?1 For an example, take multiplication: imagine you have five pizzas each cut into eight slices. Question, how many slices do you have? Well, you have 5×8=40 slices. So standard multiplication is, in some ways, just a tool for quick counting.

Let’s try some harder puzzles.

Playing Card Prestidigitation

In an effort to make math questions that pertain to everyday life, let’s consider the following situation:

You are having a pizza-poker party with your four friends (so there are five people there including you) and your best friend happens to be a world-renowned magician who specializes in card tricks named David. You, of course, ask him to do a trick before you start playing poker. He reluctantly agrees and the following happens:

David, has you pick a card and replace it while keeping it secret. David then has you shuffle the cards. Next, he asks another one of your friends to choose a card, and does the same thing, they keep it a secret and then they shuffle their card back in. This happens two more times.

David then says he’ll find all our (four) cards at once!

He takes out the ace of spades and says, “I have found all your cards!” We all are amazed because somehow, we all chose the same card: the ace of spades!

Our question: how amazed should we be? How many ways are there to take four cards out of a full deck of cards? Could this have happened randomly?

This is our common everyday counting problem.

How many ways are there to take four cards out of a full deck of cards?

How do we begin?

Let’s begin by looking at how the trick began. We chose a card and replaced it. We had 52 possible cards to take. So, if we were the only one to take a card, there are 52 ways this trick could end.

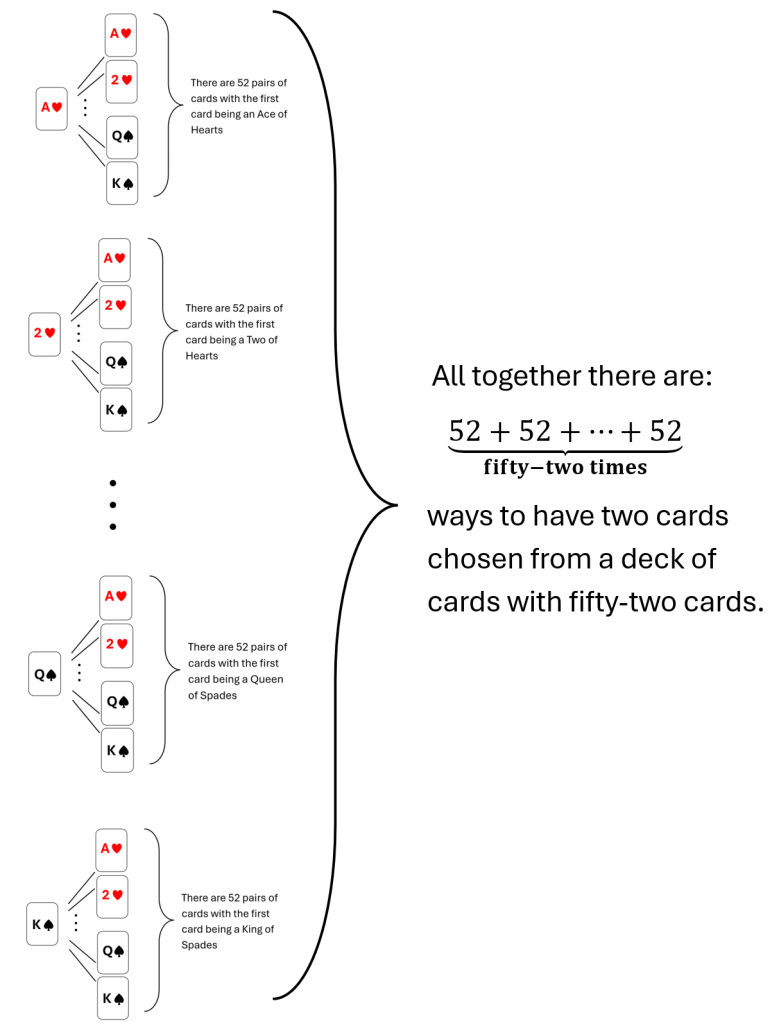

Next, our first friend does the same thing. Recall that we replaced our card back into the deck, so they also have 52 options. Thus, altogether there are 52×52 ways these two picks could happen. To see this, observe that for any card we could have taken, our first friend could then have taken any of the 52 cards. So, for example, if we took the ace of hearts there are still 52 cards our first friend could take. Or if we took the 2 of hearts, again there are still 52 cards our first friend could take. Etc. So, for each of our choices, they had 52 possibilities.

Thus, we add 52+52+52+…+52 fifty-two times, once for each of our picks. This is why we multiply 52×52.

Similar reasoning for friends three and four tells us that we have 52x52x52x52 ways this trick could happen. Since repeated multiplication happens a lot, mathematicians invented some shorthand. We write 52x52x52x52 as,

Thus, there are over 7 million different outcomes for this trick, and only one way where we could all have gotten the ace of spades. Conclusion: We should be very amazed.

Collecting Cards

David says that he has an even more amazing trick. He gives you four cards: an ace, 2, 3, and 4 of hearts. He says to shuffle them up, so they have no particular order. He says he will reveal the order whenever we stop shuffling. It so happens the cards end in the order: 2, A, 3, 4. Guess what! David guessed right! How amazing is this?

No really, how amazing is this? Especially after that first trick.

This is a new type of counting problem. We want to know how many ways there are to order four cards. The good news is that we can use similar reasoning to what we used for the previous trick.

Imagine the four holding cards. We plan to put them down on the table in some order. How many different choices do we have to put first? We have 4, since we are holding four cards. Ok, we chose our first card and put it down. We are left with three cards. By the same reasoning, we have 3 options for our second choice. After this, we have two cards and hence 2 options for the third card. Then only 1 card left for the fourth card (so we have no choice in the fourth card).

Altogether we have 4x3x2x1 ways to do this (notice that we multiply again, do you see why?). This is such an amazing counting problem that mathematicians write the answer to this problem with an exclamation point:

(Pro Tip: read 4! as four factorial) Thus, there are 24 different ways to order the five cards. Conclusion: Guessing 1 out of 24 is not as amazing as his first trick!

Pizza Possibilities

After playing poker for a while everyone at the party is hungry, so we decide to make some pizza. We have ten toppings at our disposal. However, just putting all ten toppings on one pizza is too much. So, we want to use only 4 out of the 10 toppings. How many different pizzas can we make?

This is our new counting question and, as we’ll see, it’s our most challenging one yet!

Take it easy…

When confronted with a difficult problem it’s sometimes best to try to solve a simpler version of the same problem. In this case, let’s imagine that we have five toppings that we like and restrict our pizza to only having two of them. So, we want to choose 2 out of the 5 toppings. Let’s imaginatively call our five toppings A, B, C, D, and E.

Let’s start counting.

How many options do I have to use for the first topping? There are five toppings, so I must have 5 options for what to use first.

For the second topping, since we used one, we are left with 4 other toppings to put on our pizza. Altogether, we have 5×4 = 20 different ways to put toppings on. Right? (Again, we’re multiplying.)

Another way to look at this is by using (A,B) to label choosing A and then B as toppings. We could then write out all pairs of letters. Note: We will not have a pizza with toppings (A,A) since we want two types of toppings. Our pizzas are any of the following 20 pizzas:

(A,B) (A,C) (A,D) (A,E)

(B,A) (B,C) (B,D) (B,E)

(C,A) (C,B) (C,D) (C,E)

(D,A) (D,B) (D,C) (D,E)

(E,A) (E,B) (E,C) (E,D)

Ok, so we’re done right? We have a total of 20 pizzas that we can make?

Nope!

We made one error. Well, I made the error. Look again with three hints.

(A,B) (A,C) (A,D) (A,E)

(B,A) (B,C) (B,D) (B,E)

(C,A) (C,B) (C,D) (C,E)

(D,A) (D,B) (D,C) (D,E)

(E,A) (E,B) (E,C) (E,D)

We concluded there are 20 different pizzas; however, is a pizza made by adding pepperoni and then peppers different from a pizza made by adding peppers and then pepperoni? No! They both have pepperoni and peppers, they’re the same pizza. In general, we don’t count (A,B) and (B,A) differently. We overcounted. How much did we overcount, and how do we fix this?

Consider some choice of toppings we made, say (A,B). We counted it twice, once as (A,B) and the second as (B,A). But we only want to count them once. All we need to do is divide our answer by two to get 10 possible pizzas, which are:

(A,B) (A,C) (A,D) (A,E) (B,C) (B,D) (B,E) (C,D) (C,E) (D,E)

Our Primary Pizza Puzzle

How do we generalize what we just did to our first pizza problem?

Well, let’s do the same thing. For the first topping, we have 10 choices. For the second topping only 9 since we used one. Now, for the third, we have only 8 left. Then 7 for the fourth. Altogether we have 10x9x8x7 = 5,040 possibilities.

In a similar way to before, we still overcounted but now more so. Before we only worried about over-counting pairs. Now we counted (A,B,C,D), (A,B,C,D), (A,C,B,D), (A,C,D,B), (A,D,B,C), (A,D,C,B) etc as different pizzas. Our task is to find out how many times we counted some choice like (A,B,C,D).

Observe that for some pizza choice, say (A,B,C,D) we now have a situation in which we only have four toppings. We need to count how many different ways we could put those four toppings on our pizza. In other words, how many different ways can we order four letters? This is now the same problem as David’s second trick. We concluded that there are 4! = 24 ways to order four cards. Likewise, there are the same number of ways to order four toppings, namely 24.

This means that we overcounted by a factor of 24, since for each choice in four toppings we counted it 24 times. Thus, we have 5,040/24 = 210 pizzas possibilities.

Some Final Comments

This last problem that we solved above is an example of a counting problem where we need to choose a subset of possibilities when we don’t care about their order. Another classic example is appointing a committee or making groups of students in a class. If there were ten people in a class and the teacher wanted to make a group of four students to be the class cleaners for the week it ends up being the same problem as the pizzas. Since, having Amid, Betty, Camila, and Dominic is the same as having Amid, Camila, Dominic, and Betty, in a group. Therefore, the teacher has 210 possible groups!

If you decide to look these problems up online, you’ll likely see something like,

as a way to count in these situations. This is the mathematician’s shorthand. You read the left and side as n choose k. For our pizza example, we would write 10 choose 4 (see below) because we have 10 toppings and are choosing 4 from them. The formula gives us,

Where we canceled the 6! in the numerator and denominator. The formula seems scary-looking, but it’s nothing more than the logic that we talked through. So, if you want to ignore the formula you can reason your way to an answer! You don’t need it!

I hope you had fun counting as much as I did!

P.S. Please let me know if I could have done a better job explaining anything. I would like to get better at teaching this material.

P.P.S. For another counting problem check out Permutations of: BANANAS! – A Kick in the Discovery.

Footnote:

- There are three types of mathematicians. Those who can count and those who can’t. ↩︎

Leave a comment